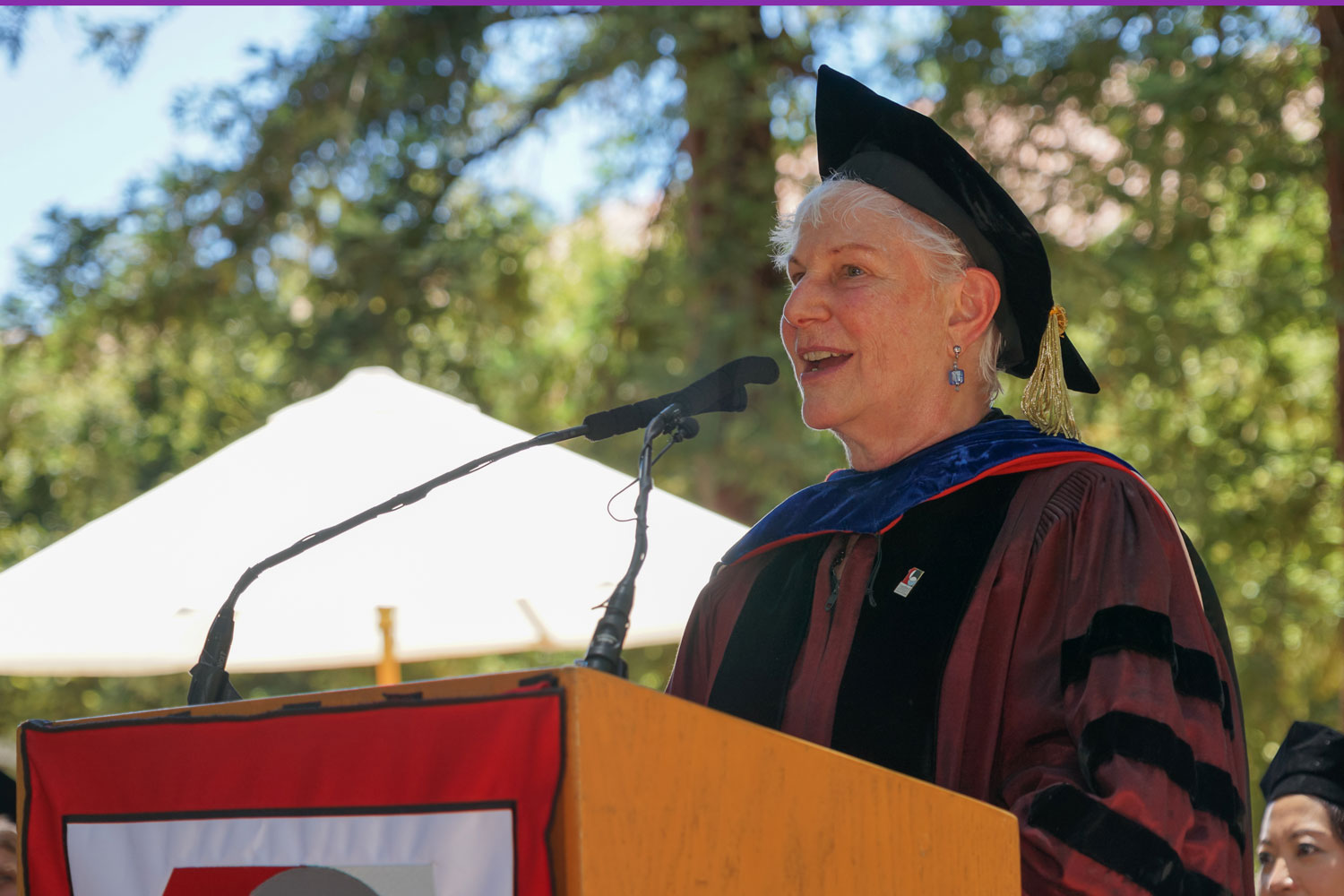

Work and family are “both greedy institutions,” but Stanford graduates are well placed to advance the ongoing argument for work-life balance and gender equity, Emerita Professor Myra Strober told Graduate School of Education degree recipients at their June 18 diploma ceremony.

“You can harmonize two careers with a successful family life, including children, if you want them,” said Strober, founder of the Stanford Center for Research on Women, today the Michelle C. Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford.

“But it is a decidedly complicated goal, and our society doesn’t help,” Strober said.

The United States is the only industrialized country without universal paid maternity leave, she noted, and has a severe shortage of affordable high-quality child care and flexible working arrangements.

In the face of these challenges, Strober urged the graduates to “prioritize what is important,” to work for change and to “try not to waste time being frustrated by trying to have it all.”

Daniel Schwartz, dean of the Graduate School of Education, introduced Strober as “a luminary in the field of labor economics.”

A leader in establishing women’s studies as a scholarly field, Strober also advanced gender equity through her inspiring example as a tenured female faculty member and through her activism on behalf of working parents. Her recent memoir, Sharing the Work: What My Family and Career Taught Me about Breaking Through (and Holding the Door Open for Others), weaves these academic and biographical strands.

Strober noted that at the start of her decades-long career, Stanford was far less hospitable to working parents than it is today.

“When I first came here as a faculty member in 1972, there was no child care at the university,” she said. She was part of a group that convinced the provost to begin providing this care. Today, she said, Stanford has child-care slots for nearly 750 children, while the State of California has greatly enhanced its family leave benefits.

Strober urged graduates not only to live and seek work-life balance but also to teach it.

“As you go forward, I hope you will work hard to make it possible not only for you to harmonize work and family, but also for others, with less education and less clout to do the same,” she said.

“I hope you will work both in your own workplace and in the political arena for subsidized high quality childcare, paid parental leave, and an end to discrimination against part-time employees.

“I hope you will be among those who work to create new models.”

Strober said that as a graduate of Stanford, “you are now among the most privileged people in the world. You may not have started life as a privileged person, but you have become one.”

She urged graduates to use that privilege to work for change, “not only for yourself and your family, but for those whose voice is less powerful than yours.”

The historical perspective is especially apropos as the GSE celebrates its centennial in 2017. Stanford was one of the first U.S. universities to include a department of education when it opened in 1891. Elevated to a school in 1917, today’s GSE soon became a leader in research, practice and policy.

In exhorting graduates to assume that mantle, Schwartz cautioned that getting the world to embrace new ideas is not always easy.

“One thing you will all have in common is that your work will be impeded by people who claim they know whatever you have to say,” he said.

Yet, as befitting an educator, Schwartz used the occasion as a teachable moment.

“The key move is to get people to commit before you tell them the finding. It is called a ‘stinger.’ Here’s an example that comes from a kindergarten teacher who once played this game on me.

“Please finish the following, ‘Practice makes _______.’

“Perfect,” ventured the crowd.

Said Schwartz: “The kindergarten teacher smiled and said, ‘No, practice makes permanent. Practice with feedback makes perfect.’

“So, ‘If at first you don’t succeed,’ what?” Schwartz asked.

“Try again,” came the response.

“Try a new approach,” Schwartz replied.

“An ongoing challenge will be how to help them experience needs for new learning, when they have comfort in the old,” he said. “Do not get frustrated – get creative.

“You’ll hear things that aren’t quite true and you’ll navigate when to step in and correct them. You’ll see people being treated unfairly, and you’ll aim to remedy it. You’ll create new knowledge whether in books or one-on-one interactions. You’ll create new programs or companies. You’ll become leaders in your schools and in your work. “

The school conferred 29 PhDs and 181 master’s degrees in academic 2016-17.

Among the PhD recipients was Eliza Evans, who received her degree posthumously after her death in August 2016 of metastatic breast cancer. Evans’ doctoral colleagues honored her with a standing ovation when her name was called on the roll of degree recipients by Associate Dean Bryan Brown.

This week, the GSE also recognized 18 graduating seniors who completed the undergraduate minor or honors in education. The eight honors students successfully completed a supervised research thesis as well as coursework in the school. At a special ceremony Friday, June 16, they all received honor cords of azure blue – the traditional heraldic color of education – to wear with their academic robes on Commencement weekend.

New PhD Susana Claro walked in Sunday’s processional with her beaming 6-year-old son, Emilio Ibañez.

“I told him this was my reward for doing graphs. He likes graphs,” Claro said.

Tyler Knapp, who earned her master’s in the STEP (Stanford Teacher Education Program) Elementary program, festooned her mortarboard with paper butterflies that symbolized resilience amid challenge. Though Knapp hails from nearby Palo Alto, her father’s serious illness kept her family from attending the ceremony.

“Today, my butterflies make me feel I have my family around me,” she said.

Schwartz urged the graduates and their loved ones to feel a familial sense of unity.

“We are your people – beside you, in front of you, behind you, behind me – bound together by a commitment to education,” he said.

“You are part of its legacy and its future,” he said. “So go make all of us proud.”

____

Photos by Hiep Ho and Marc Franklin

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.