Identifying patterns and differences

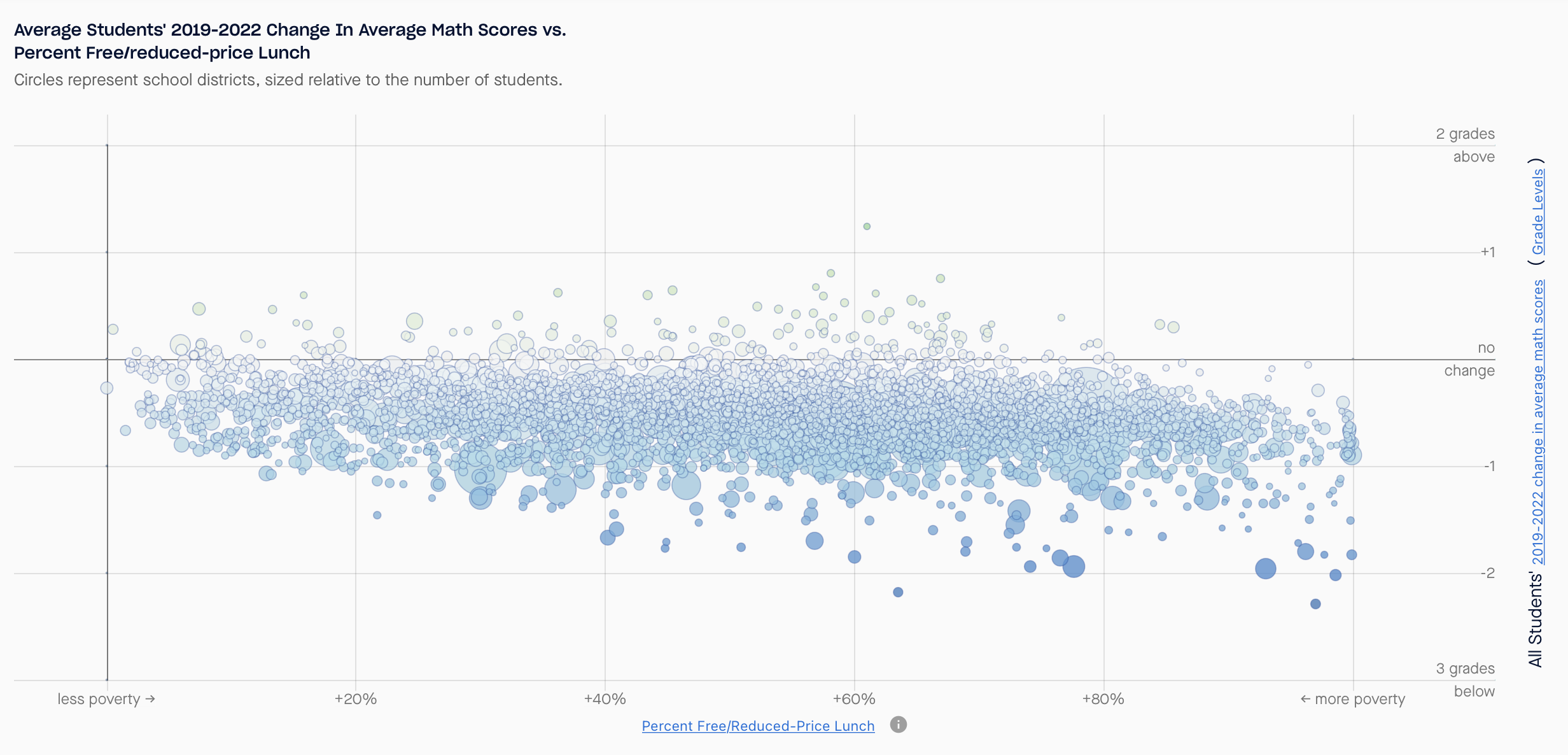

The district-level analysis indicates that the pandemic exacerbated educational inequalities based on income, showing the most pronounced learning losses among students in low-income communities and school districts.

The analysis also showed that test scores declined more, on average, in school districts where students were learning remotely than where learning took place in person. But the extent to which a school district was in-person or remote was a minor factor in the change in student performance, the researchers found.

“Even in school districts where students were in person for the whole year, test scores still declined substantially on average,” said Reardon, noting the toll that pandemic-related disruptions took on students’ routines, family and social support, and mental health. “A lot of things were happening that made it hard for kids to learn. One of them seems to be the extent to which schools were open or closed, but that’s only one among many factors that seems to have driven the patterns of change.”

The data analysis was conducted by the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University (EOP), an initiative launched by Reardon in 2019. The EOP houses the Stanford Education Data Archive (SEDA), a comprehensive national database of academic performance first made available online in 2016. Since then researchers have used the massive data set, which contains standardized reading and math test scores from students in every public school in the nation, to study variations in educational opportunity by race, gender, and socioeconomic conditions.

To generate a district-level analysis of pandemic learning loss, Reardon’s team applied an approach they developed to produce estimates of student performance that are comparable across places, grades, and years – a challenge given the discrepancy between assessments used in different states from year to year.

In addition to administering the NAEP every two years, all states are required to test students in third through eighth grades each year in math and reading, and to make the aggregated results of those tests public. Because most states use their own annual test (and define “proficiency” in different ways), researchers generally can’t compare these yearly test results from one state directly with results from another.

Reardon’s team developed a research method to overcome that challenge: By aligning the annual statewide test results with scores from the biennial NAEP, his team produces data that can be compared across states. “We use state tests to measure district-level changes in academic skills, and the NAEP test serves as a kind of Rosetta Stone that lets us put these changes on the same scale,” Reardon said. “Once we equate the tests from different states, we can make apples-to-apples comparisons among districts all over the country.”

Using demographic data also housed in SEDA, the researchers can estimate how scores within an individual district compare with statewide and national averages. They can also identify trends among various subgroups of students, including racial/ethnic and socioeconomic.

For the Education Recovery Scorecard, the research team obtained annual test scores from 30 states – all that have, to date, reported their districts’ proficiency rates for their spring 2022 assessments. The remaining states will be added to the analysis as their data becomes public.