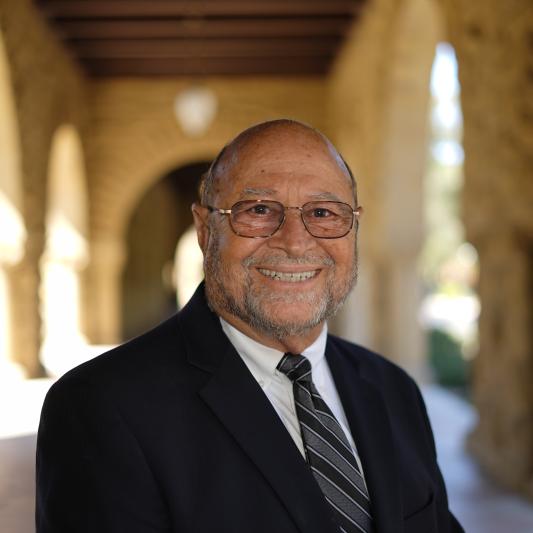

David Berliner, PhD ’68

David Berliner, PhD ’68, brings psychological advances to his study of teaching and impassioned rigor to his ongoing defense of public schools

Eminence in research and advocacy

David Berliner, PhD ’68, brings psychological advances to his study of teaching and impassioned rigor to his ongoing defense of public schools

By Barbara Wilcox

After decades of research and writing that made him a leader in educational psychology, David Berliner in the early 1990s felt both qualified and compelled to speak on the state of America’s public schools.

Dubious for years of the methodology behind A Nation at Risk, a 1983 White House commission report blasting U.S. schools, Berliner gave a speech at an academic convention denouncing the report and its use in attacks on public education.

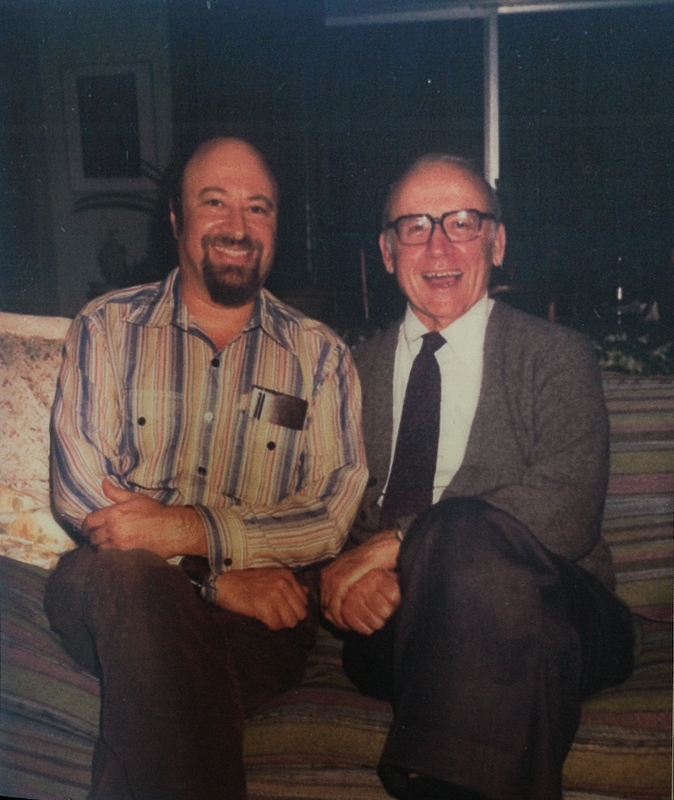

He was accosted after his talk by Prof. N.L. Gage, his textbook collaborator and former mentor at Stanford.

“Gage looked me squarely in the eye,” Berliner wrote in an essay on his Stanford years, “and said, with a touch of sadness about my errant behavior, ‘David, you need data if you are going to say things like that.’”

The result was The Manufactured Crisis, which Berliner coauthored with Bruce Biddle in 1995 as the first detailed evidence-based refutation of the 1983 report. The book catapulted Berliner, an Arizona State University professor already renowned for his research on expert teaching, into a new career phase as public advocate of public schools as essential to democracy. Other books followed as Berliner, dean from 1997 to 2001 of ASU’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, continued to attack what he sees as the true foes of good schools: insufficient investment, confidence and even interest in public education, and economic inequality that yields unequal opportunities to learn.

For his longtime leadership in both research and advocacy, the Stanford Graduate School of Education honors Berliner in 2017 with its first Lifetime Achievement of Excellence in Education Award.

“Much of the purported evidence in educational research is confusing to decision-makers, policy-makers, politicians and laypersons,” said emeritus Prof. Henry M. Levin, now at Columbia University. “David has become the top ‘translator’ of educational research for these audiences.”

As a scholar, Berliner pioneered the application of cognitive psychology to the study of education, said former School of Education Dean Richard Shavelson. As a policy analyst, Shavelson said, “David is in the trenches. His policy work is first-rate. His balance is welcome in the educational world.”

To Berliner, it all began in “the wonderful habits of mind” he learned at Stanford, especially from mentors Gage and Prof. Lee Cronbach, both of whom continue to perch on Berliner’s shoulders as dual aspects of a professional’s conscience.

“They were very different people,” Berliner said. “One was a positivist. One was a negativist. Nate always believed research could solve humanity’s problems. Lee always thought that research was overplayed, that’s it hard to do research as social scientists.

“They were both right.

“Habits of mind are very different than knowledge,” Berliner said. “Habits of mind are ways of structuring the world, ways of thinking about the concepts that make up your field. The professors I worked with had enormous influence on the way I think about the problems of teaching and assessment. My mentors just thought differently, and their standards were very high.

“I remember getting a paper back from an eminent professor here at the GSE, who gave me an A in a course. I was very thrilled to be one of his top students. But on my paper was written, ‘Good but short of eminence.’

“So I go through life trying to figure out what eminence is.”

As a new PhD teaching in rural Massachusetts, Berliner and his family found they missed the West. He left his tenure-track post to return to Palo Alto for a job held jointly between Stanford and Far West Laboratory. In off hours, he and Gage worked on what eventually became a foundational textbook of educational psychology.

“The book came out of my hide,” Berliner said. “We worked all day every Friday and Saturday for about five years until we got the first edition. But what more could a scholar want than intimate time with another scholar? We sat around and discussed wonderful ideas. Perhaps that was why it took five years!”

Their introductory text Educational Psychology went through six editions and became one of the best-selling texts in its field, internationally as well as in the United States.

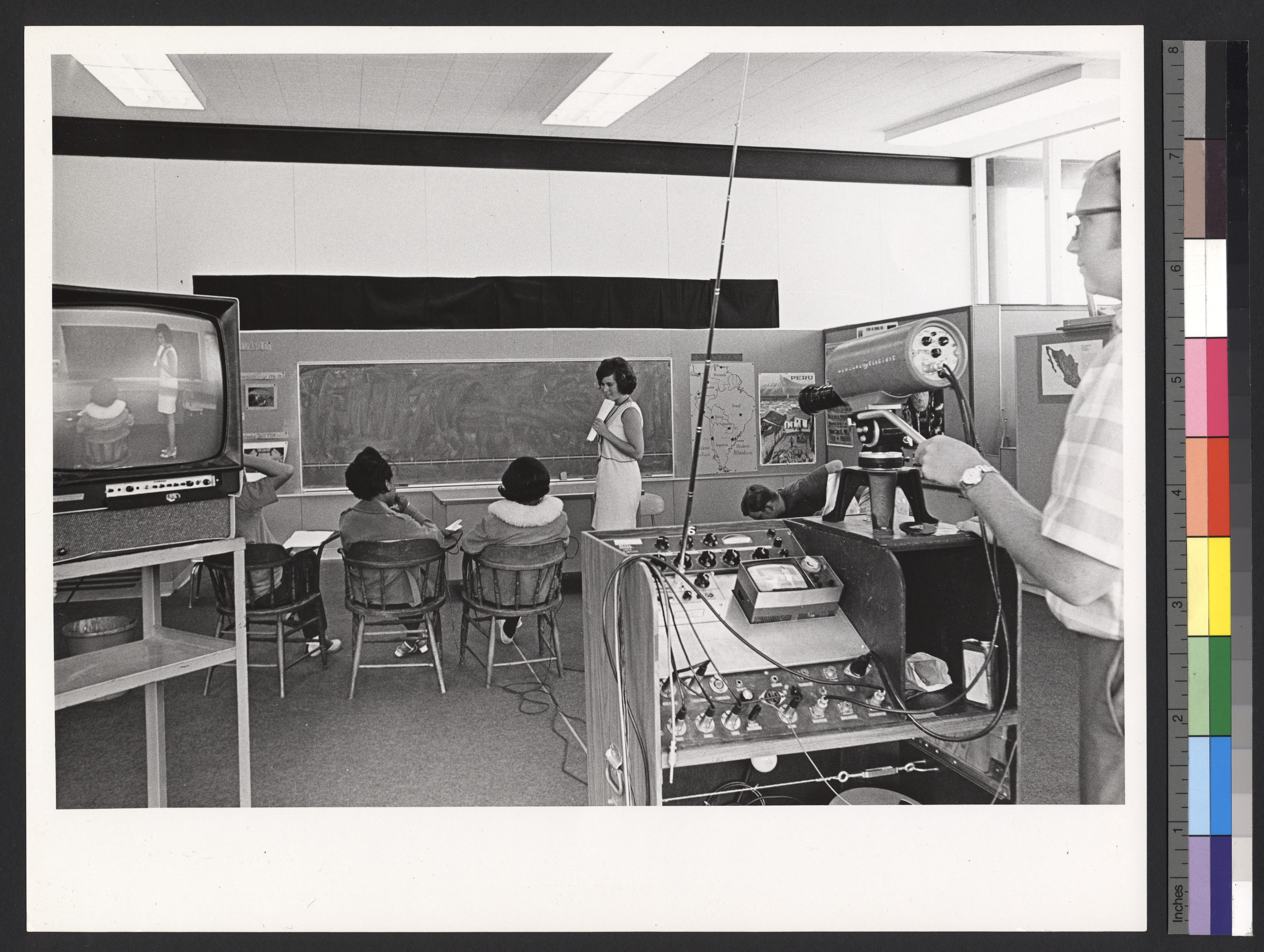

The research for which Berliner is best known, on teacher expertise, was an outgrowth of a large study evaluating beginning teachers.

“That project took me into a lot of classrooms, probably 150 to 200 during the course of the study. Every once in a while I’d stumble into a classroom where I’d just say, ‘Wow! How did they do that?’ The first cognitive-psychological research on experts was just coming out – experts in chess, in athletics, and so on. Yet nobody had thought about teachers as having many of the same qualities of expertise.”

For example, Berliner showed photos of elementary classrooms to teachers who were rated as experts, or were beginning their careers – novices. He found that the experts, by looking at a single picture, could provide far more detailed accounts of how the classroom was being organized and managed. Novice teachers merely described accurately what they saw.

From this study came findings that expert teachers behave in unique ways. Their remarkable skills can be analyzed and described, and – a key point, Berliner maintains – these expert teachers deserve to be respected for their remarkable competence.

Meanwhile, however, he became increasingly aware of the limits of research’s reach. He spent a good deal of time in K-12 schools – visiting many as ASU dean to learn how its teacher graduates are doing – and urged other scholars to do the same.

“Education is not run by our scholarship as much as it is by the politics of our times,” he said. “Classrooms are affected by housing policies, legal policies, transportation policies, employment policies. If we’re working on the economics of education or on learning theory, we’re pretty far removed from what it is we hope to improve.”

In a follow-up book, Collateral Damage (2007), coauthored with Sharon Nichols, he chronicles the results of using high-stakes testing to punish schools whose main offense is being socioeconomically deprived. A third book, 50 Myths and Lies That Threaten America’s Public Schools (2014), co-written with Gene Glass, skewers America’s infatuation with rankings, with STEM to the disadvantage of other liberal arts, and with charter schools that raise their graduation rates by shedding underperforming students – something conventional public schools are far less able to do.

“I’m a bit of a New Yorker and getting in someone’s face is fun,” Berliner said. “If someone says something untrue about public schools, I’m right there. 50 Myths and Lies is really about saying to people, ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about.’

“Yes, education costs money. But the return on investment, every economist tells us, is enormous. People with a decent education don’t get incarcerated as much. Marriages hold together better. They hold their jobs longer. Their children are raised better. These are all outcomes of adequate public schools. And of course supporting those schools is costly.

“Just as highways and airports need money, so do our public schools. And so do our teachers. We have to take better care of our schools and the teachers in those schools in order to maintain the kind of democracy the way most of us want.”

Learn more about Berliner’s Stanford years in The Ones We Remember: Scholars Reflect on Teachers Who Made a Difference.

Read Berliner’s take on the role of poverty in school reform.

Watch Berliner on video at Simon Fraser University.

For more information about the GSE Alumni Excellence in Education Award reception, and to register for this special event, please visit the GSE’s Reunion Webpage.