Jonathan Jansen, PhD ’91

Jonathan Jansen has been inspiring students throughout South Africa with a lesson he learned at Stanford: Aim high and think big.

Healing a campus post-apartheid: An educator fosters new era for universities in South Africa

Jonathan Jansen has been inspiring students throughout South Africa with a lesson he learned at Stanford: Aim high and think big.

By Joyce Gemperlein

It is as though Jonathan Jansen, who was living a self-described “miserable, horrendous” childhood in apartheid South Africa, was startled from sleep the day his 8th grade teacher said he saw potential in the boy.

“I did not know what ‘potential’ was — my mother translated the word to mean that I could do more than play soccer for the rest of my life,” said Jansen PhD ’91 in a telephone interview from his office in Bloemfontein, South Africa, where he is vice-chancellor and rector of the University of the Free State (UFS).

Jansen has done so much more, in fact, that he is one of three Stanford Graduate School of Education graduates chosen for its inaugural Alumni Excellence in Education Award. Along with Helen Kim ’92, MA ’93, and Carla Pugh MD, PhD ’01, he will be formally recognized for transformational work in education at an Oct. 23 reception during Reunion Homecoming weekend. They were singled out for the honor in a peer-nomination process with selection and review by the GSE dean, faculty and a committee of leading alumni.

Upon hearing of the award, Jansen thought “a mistake had been made,” he said.

Jansen is well known for such humility in the face of overwhelming evidence that he is a champion of intellectual freedom and a powerhouse in South African education and the racial politics accompanying it.

It is a role he unknowingly began preparing for when he was born in Cape Town in 1956, eight years after apartheid began. His neighborhood, Cape Flats, was windswept, poor and violent.

Jansen was one of five children of a domestic worker, later a driver, and a nurse who reared him in “a bubble of decency” amid constant harassment of blacks — often by unwarranted police brutality. He witnessed humiliation, murder, rape and suicide. The family’s property, owned for generations, was appropriated by the state as part of a strategy to disempower blacks. He was intensely religious, but he does not deny that he was an angry young man.

And yet, Jansen finished high school fueled by the encouragement of that 8th grade teacher. He went on to dodge bullets, fists, racism and harassment at university during the time of the 1976 Soweto uprising which spread throughout the country including the University of the Western Cape where he was a student pursuing a bachelor of science degree.

“I then decided to teach,” he said. “Within five minutes of entering my high school biology classroom, I knew this was what I wanted to do. I still feel it’s the best thing any person can do to change minds, to give young people idealism and energy and nurture the senses of risk and ambition.”

He was enmeshed in the lives of his students, even visiting them in the hospital when they were victimized during violence prior to the dismantling of apartheid.

Forgiving past transgressions

In 1985, one year after the country’s first general elections, Jansen came to the attention of Archbishop Desmond Tutu and American activists, who selected him for a scholarship at Cornell University.

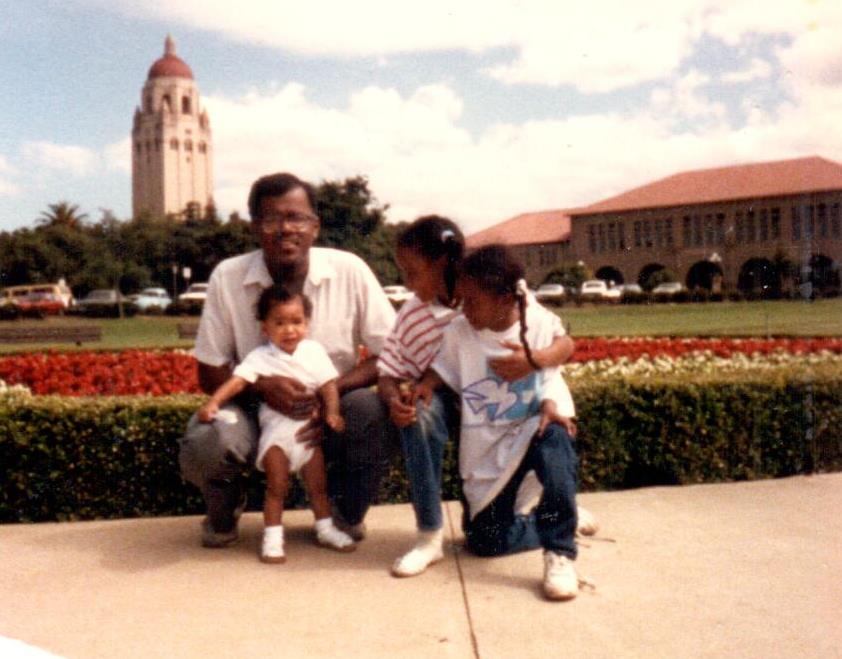

He then came to Stanford in 1987 to pursue his doctorate. His dissertation analyzed curriculum reform in Zimbabwe, “distinguishing what factors inhibit radical change, from an inherited curriculum to something more progressive.” While at the GSE, he also examined education systems in Nicaragua, Cuba and Tanzania.

In 2009, after what he recalls as a 15-minute telephone invitation, Jansen applied and became the first black president of the historically white — but gradually integrated post-apartheid — UFS, which has three campuses and more than 31,000 students from 40 countries. It was a step up from his previous post as dean of education at another former white institution, the University of Pretoria, where he had played a leading role in integrating the campus. And it posed an even greater challenge.

Jansen arrived at UFS to find that reconciliation between white Afrikaner and black students was in turmoil even though Nelson Mandela had earlier declared the school a model of post-racial transformation.

There had been incidents of violence centering on race, religion and culture. In a few years’ time, students had self-segregated themselves on campus — especially in the dorms. An ugly incident involving white students hazing black workers who clean the residences had shown up in an online video.

It was against that background that Jansen was portrayed in South African media as “a healer,” Eve Fairbanks, a South African journalist, wrote in a feature story about him in The New Republic in 2010.

To much skepticism, Jansen announced plans to forgo revenge and instead forgive past transgressions. He vowed to foster black-white empathy “by refashioning the university’s culture into a bridge” where whites and blacks meet perfectly in the middle. He made the case that every white student should learn to speak Sesotho, the local Basotho language, and every black student should learn Afrikaans.

He ordered that every dormitory would be 50/50 black/white to break the segregation practices that had developed in them.

The main campus of UFS is now more than 65 percent black. The country is more than 80 percent black.

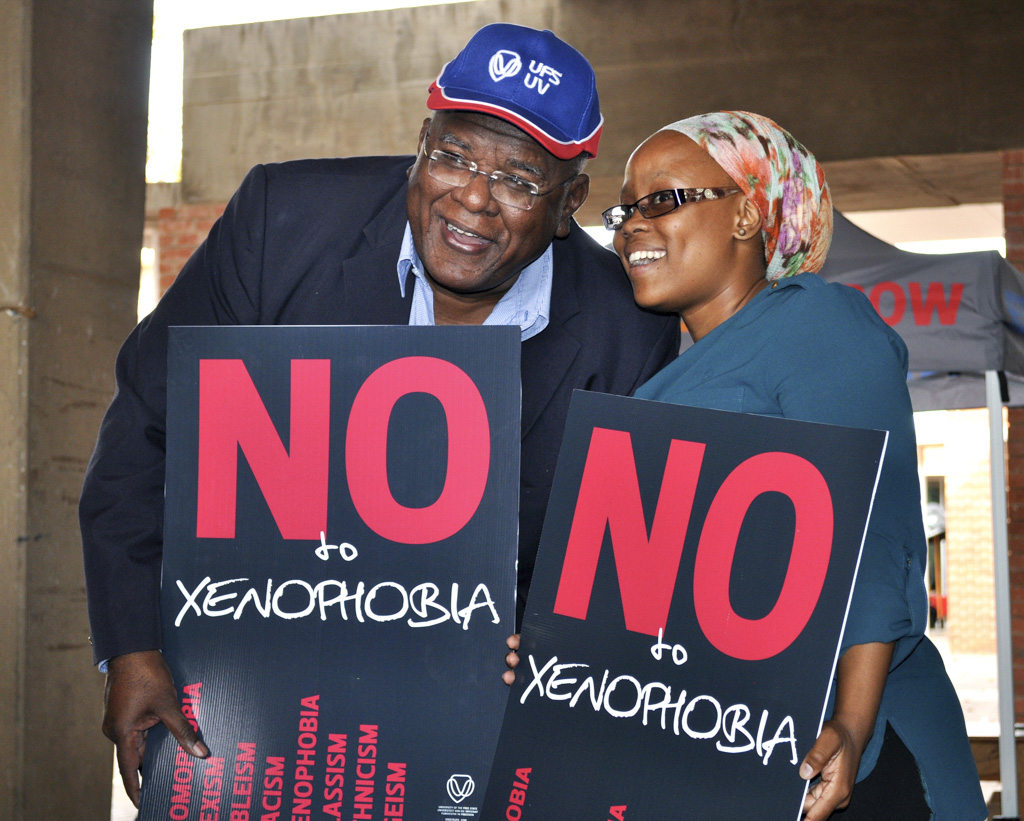

Jansen instituted a credo of what he calls “change during peacetime,” which he defines as not merely reacting to bigoted or violent situations when they happen, but to lay the groundwork beforehand for reconciliation through regular discussions about experience, bitterness and stereotypes — “to learn not just to tolerate, but to embrace each other.”

He set out to make the school “a model to the country of how to create interracial community despite our divided past,” he said.

Jansen convened regular campus-wide discussions among students and faculty and advised that situations should be judged in context without singling out individuals because they “act with the complicity of history.”

When Fairbanks revisited the campus in 2013, she wrote in another story that Jansen had substantially earned the “healer” moniker given him upon his arrival on campus.

A public intellectual with a personal touch

Bianca de Koning, 20, a white student at UFS, said Jansen’s style of leadership is “fatherly,” warm, open and inclusive to every student. She said he often holds impromptu meetings on the lawn or has lunch with students and answers any question put to him. Last summer he manned an ice cream truck to serve students himself on each of the school’s campuses.

The house where he lives with Grace, his wife of 32 years, is a hangout for undergraduates, with weekend events such as swimming, volleyball and drumming. Grace Jansen volunteers at No Student Hungry, a university program that helps students who risk dropping out because they cannot afford food. His children — Mikhail, born during the Jansens’ Cornell years; and Sara-Jane, during their time at Stanford — inherited their parents’ social consciousness. Mikhail is an educational psychologist who works with South African special needs children, and Sara-Jane, who lives with her parents, is a social worker for young people who are distressed and marginalized in their communities.

Jansen — and his family — model instincts and humanity that earn praise from former colleagues at Stanford.

J. Myron (Mike) Atkin, emeritus professor and a former GSE dean, called Jansen a model “public intellectual,” an academic working to affect public policy. He has not hesitated to publicly criticize the non-apartheid government when he has perceived that it was creeping toward re-sorting people, Atkin noted.

“A lot of what he says directly tackles situations we need to address in the United States," said Ann Lieberman, senior scholar at the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education, who praised Jansen as "a very independent thinker” with great wisdom about how to live in a multiracial society.

Martin Carnoy, Vida Jacks Professor of Education, said Jansen “has done a remarkable job in South Africa. He is open and frank with everyone, and because he takes the position that racism is a two-way street for both whites and blacks, he has gained enormous admiration across South Africa.”

Jansen is a fellow of the American Educational Research Association and a fellow of the Academy of Science of the Developing World. He has authored many books, including Knowledge in the Blood: Confronting Race and the Apartheid Past (Stanford 2009) declared one of the best books of that year by the American Libraries Association. The book, a memoir as well as a scholarly analysis of race relations and higher education, details his eight-year tenure as the University of Pretoria’s dean of education during which he led the difficult integration of what was a bastion of Afrikaner higher education.

He is President of the South African Institute of Race Relations and was vice-president of the Academy of Science of South Africa, where he led a study about the future of the humanities in South Africa, among other projects.

In another of his books, How to Fix South Africa’s Schools: Lessons from Schools that Work (Bookstorm 2014), he uses video recorded in select schools that serve disadvantaged students to document and spotlight the methods that are producing some of the nation’s best physical science and mathematics students.

“We have the same problem as the United States of having systems that work for 20 percent of the students,” Jansen said. One of his solutions to help the remaining 80 percent is sending the best and most experienced retired teachers into schools to mentor principals and educators.

His latest book is Leading for Change: Race, Intimacy and Leadership on Divided University Campuses (Routledge 2015) and describes the transformation of race relations among students at the UFS over a six-year period.

Bringing Stanford to South Africa

Jansen conceded that reform does not occur overnight.

“Yes, life in South Africa is very different now. We are a democracy; we can vote for the first time, can speak without consequence and live where we want. But we carry the scars of past issues of racial segregation and division — as in the United States and around the world,” he said.

He added that he hopes post-apartheid South Africa and UFS will someday be considered templates for handling worldwide conflicts springing from race, stereotypes, religion and culture.

Jansen credits his time at the Graduate School of Education — “the best decision I made in my entire life” – with giving him skills, confidence and connections to help his homeland.

He added that he is humbled to receive the award and is looking forward to receiving it later this month at Stanford, which he calls “a place of intellect and passion that has the knack of taking people and making them do exceptional things.

“The whole environment gives you a sense of aspiration beyond what you can even dream and that is what I have tried to bring back to South Africa.”

He said he tries to describe the atmosphere at Stanford to students who are headed there to participate in the Stanford Sophomore College Program, which mingles six UFS students yearly with Stanford peers. It is only when they return that they say: “’NOW we understand what you mean!’”

When his time at UFS ends in a few years, he said he will continue to perform what he thinks of as “ploughing back.” He defines this as finding, encouraging, inspiring and investing students who remind him of his former self: They need opportunities to realize what they are able to accomplish.

Bianca de Koning is one such student. Jansen read of her plight in a newspaper: Despite being at the top of her high school class, she was unable to attend university because her family was destitute and plagued by health issues. He telephoned her and awarded her a full scholarship. She is earning top honors at her double-major in genetics and psychology and has made close friends without regard to race.

Jansen said he will always be on the lookout for more Biancas.

Because, like his 8th grade teacher, Jansen said he knows potential when he sees it.

Joyce Gemperlein, a freelance writer in the Bay Area and a former Knight Fellow at Stanford, is a contributor to the Educator, the online newsletter of Stanford Graduate School of Education. Please read our previous issues and subscribe.

All photos are courtesy of Jonathan Jansen and the University of the Free State.