Editor's note: This story was updated Feb. 3 with information about a GSE memorial service.

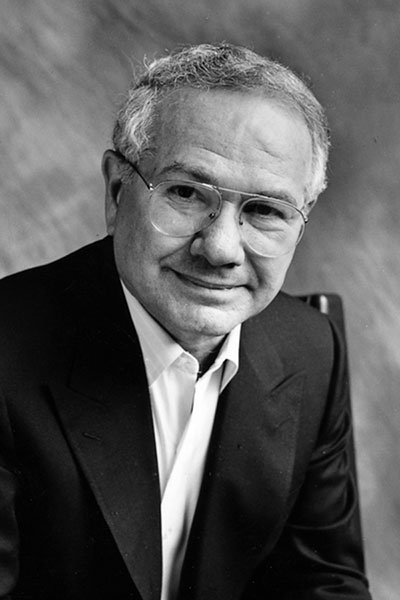

Elliot Eisner, a leading scholar of arts education who presented a rich and powerful alternative vision to the devastating cuts made to the arts in U.S. schools in recent decades, died on Jan. 10 at his home on the Stanford University campus from complications related to Parkinson's disease. He was 80.

Over the course of his academic career, Eisner, the Lee Jacks Professor Emeritus of Education at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and Professor Emeritus of Art, championed ways that the arts could benefit student learning, as well as educational practice.

He maintained that the arts are critically important to the development of thinking skills in children and that the arts might offer teachers both a powerful guide and critical tool in their practice. He wrote 17 books and dozens of papers addressing curriculum, aesthetic intelligence, teaching, learning and qualitative measurement, in addition to his frequent and entertaining lectures throughout the nation and abroad.

Eisner’s ideas reached beyond academia into the classroom: the National Art Education Association, of which he served as president, turned his list — "10 Lessons the Arts Teach" — into a poster, which can still be found today hanging on school walls nationwide. Among the lessons: the arts teach students that small differences can have large effects; the arts celebrate multiple perspectives; and the arts teach children that in complex forms of problem solving, purposes are seldom fixed but change with circumstance and opportunity.

"To neglect the contribution of the arts in education, either through inadequate time, resources or poorly trained teachers is to deny children access to one of the most stunning aspects of their culture and one of the most potent means for developing their minds," Eisner wrote.

Eisner eschewed the more popular argument for the arts — that some research showed music, dance, and painting actually boosted test scores in math and science.

Eisner, rather, talked about art for art's sake.

"He figured out that there was something missing from mainstream educational theory and method," said his friend and Stanford colleague Professor Raymond McDermott. "He wanted to address matters of the heart, whereas most of the discipline was pushing a more mechanical view of the child and the act of teaching or researching."

Eisner reached into areas that sat on the margins of educational discourse: arts education, most literally; the art of education, by extension; and the art of researching education, most controversially, McDermott said.

"He moved these concerns to the front and center," McDermott said.

Eisner's unrelenting advocacy of the arts continued during periods in which arts programs were cut in schools, and a chorus of administrators and policymakers, faced with budget constraints, focused on test scores, worried that spending time painting or drawing was not academic enough.

"One of the casualties of our preoccupation with test scores is the presence — or should I say the absence — of arts in our schools," he wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2005. "When they do appear they are usually treated as ornamental rather than substantive aspects of our children's school experience. The arts are considered nice but not necessary."

Eisner advocated a strict, more sophisticated and rigorous arts curriculum that would put arts instruction on par with lessons in reading, science and math.

Eisner was born in Chicago on March 10, 1933. From an early age, he was set on pursuing a career as an artist. He graduated in 1954 from Roosevelt University in Chicago with a BA in art and education and the following year received an MS in art education from the Illinois Institute of Technology. He then spent two years as a high school art teacher and discovered that he was more interested in the students than the actual art they were making.

He returned to graduate school in the late 1950s, receiving a master’s degree and doctorate in education from the University of Chicago. Eisner served as an assistant professor there before joining the Stanford faculty in 1965.

Along with his lectures, writings and teaching, his involvement in such curriculum initiatives as the Kettering Project at Stanford in the late 1960s and the Getty Center for Education in the Arts in the 1980s brought him wide recognition, helping him become an influential voice for teachers, scholars and other educators.

Eisner proposed that the forms of thinking needed to create artistic work were relevant to all aspects of education. Incorporating methods from the arts into teaching of all subjects would cultivate a richer educational experience, he said.

"The arts are fundamental resources through which the world is viewed, meaning is created, and the mind developed," he wrote.

His work with the Getty Center advanced what is called Discipline-Based Art Education. The curriculum structure advocated in DBAE stresses four aspects of the arts: making it, appreciating it, understanding it and making judgments about it.

This type of arts education, Eisner argued, would result in children better understanding the relationships between culture and art and becoming more artistically literate. He also believed children's conceptions of what knowledge is would be more sophisticated after this type of inquiry.

"His voice for evaluating teaching and student learning through many means, not just standardized testing, continued to be heard during the past three decades of standards-based school reform, testing and accountability," said Larry Cuban, professor emeritus of education at Stanford. "Eisner's eloquence in writing and speech gave heart to and bolstered many educators who felt that the humanities, qualitative approaches to evaluation and artistic criticism had been hijacked by those who wanted only numbers as a sign of effectiveness."

For his achievements, Eisner was honored with the Palmer O. Johnson Memorial Award from the American Educational Research Association, a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, a Fulbright Fellowship, the Jose Vasconcelos Award from the World Cultural Council, the Harold W. McGraw Jr. Prize in Education from the McGraw-Hill Research Foundation, the Brock International Prize in Education, and the University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Education and five honorary degrees. He served as president of the International Society for Education through Art, the American Educational Research Association, and the John Dewey Society. And he was a member of the Royal Society of Arts in the United Kingdom, the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters and, back in the U.S., the National Academy of Education.

Former GSE Dean Rich Shavelson described Eisner as a "renaissance man."

"He had big ideas and he could communicate those ideas. He was often a lone voice in the wilderness, debating, sharing. He argued cogently and forcefully and challenged existing ideas at every chance," Shavelson said.

"He saw art in everything," said his daughter, Linda Eislund. "He wanted people to think critically about things, ask questions, learn with all their senses."

Added his son, Steve Eisner, a Stanford alum and the university's Director of Export Compliance and Export Control Officer: "He saw the arts as a way to help individuals realize their potential. He was extremely dedicated to his students and their understanding of how the arts can influence cognition and creativity. He saw them as a way to continue his life’s passion, namely advocacy for the arts."

In addition to his son and daughter, Eisner is survived by his wife of 57 years, Ellie; son-in-law Eric Eislund; and grandsons Seth and Drew Eislund and Ari Eisner.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to the National Art Education Association's Elliot Eisner Lifetime Achievement Award, established by the Eisners to recognize individuals in art education whose career contributions have benefited the field. The address for the NAEA is: 1806 Robert Fulton Drive, Suite 300, Reston, Virginia 20191.

Contributions will also be gratefully received for the Parkinson's Disease Caregiver Program, Department of Neurology, Stanford University Medical Center, 3172 Porter Drive, Suite 210, Palo Alto, CA 94304.

A memorial tribute is planned for March 3 at 11 a.m. in Cubberley Auditorium at the Stanford GSE. A reception will follow at 1 p.m. Please RSVP here by Feb. 17. The American Educational Research Association also is planning a memorial symposium during its annual meeting April 3-7 in Philadelphia.

Comments

Elliot created a field.

Elliot created a field. Elliot also wanted to create better people, and on their terms. I only had a chance to speak with him a handful of times. Each time, he wanted to hear about me, about my work, about my ideas. I would ask him what he thought about this and that. He would have none of it. He wanted to engage my ideas to help me become what I might possibly become. I often wondered if the young Elliot was so giving, and what fearful heights he might reach if contradicted. I don't think I'll ever know, but I got a hint once when I mentioned that I felt I had not written something "buttery smooth" (his words). That... the lack of art in authorship... was clearly not OK. We both smiled. A man of strong beliefs, yet a sweet prince. Sleep well.

~~ I took his class in

~~ I took his class in Curriculum Theory and was his RA in 1978. You had only to be in his presence to learn from him. Part of my RA duties’ was to assist with the organization of a conference for local teachers to whom he was very committed. We spoke much about teachers, students and their learning. His views on learning were expansive and inclusive and his voice was loud and strong in defence of an education that would open the mind rather than close it. His 2002 address to the John Dewey Society summed it up:

“Our destination is to change the social vision of what schools can be. It will not be an easy journey but when the seas seem too treacherous to travel and the stars too distant to touch we should remember Robert Browning’s observation that “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp or what’s a heaven for.”

His words live on as does his quest. What a privilege it has been to have known this man!

Ellie, You have my deep

Ellie, You have my deep sympathy as we just saw on Stanford Report that your husband, Elliot died. We last saw you, two, at the Stanford Faculty Club having lunch and has a pleasant conversation with you there. You both are our neighbor for about 44 years and he will be deeply missed. He was a nice neighbor and we enjoyed seeing him driving his sports car down the street.

Sheralee Hill Iglehart, B.S., M.A.

Stanford, California

My heart is deeply saddened

My heart is deeply saddened with the passing of this great man, scholar, and friend. I worked for and with him at GSE, then SUSE. I always thought that I received a private PhD with Elliot. He carefully and thoughtfully put each word on paper to ensure he made the most cogent and impact full argument or point. His love of the arts was exhibited in every aspect of his life. I treasure every moment I spent with him and Ellie. Once he sang "Seems like old times" to me when I returned for a second round of working for him. I loved this man and will hold our times together close to me for the rest of my life. This is a huge loss in the academic world and for so many whose lives he touched in significant and profound ways. Love to Ellie, Linda, and Steve, the family he treasured.

Dear Ellie, Linda, and Steve,

Dear Ellie, Linda, and Steve,

My heartfelt condolences to you. Elliot was such a wonderful man. So talented and accomplished. I sm sorry for your loss.

The Sage handbook of

The Sage handbook of philosophy of education (2010) has a "Gazetteer of Educational Thinkers" which has an entry on Elliot Eisner sandwiched between Durkheim and Erasmus. When I told Elliot about this he really wasn't very interested--not at all the sort of man to puff himself. What did interest him was children and art. I witnessed this first hand at an exhibit of art by Paly students one year. Not only was he there and clearly engaged, but his name was on everyone's lips before he got there. I feel privileged to have known him even for such a short time.

As a science teacher, I was

As a science teacher, I was influenced by Dr. Eisner's work. The arts are integral to all human endeavor.

I will miss seeing Elliot at

I will miss seeing Elliot at GSE functions where he--and Ellie--could always be depended upon to be surrounded by alumni and other friends in lively conversation. I think the last time I saw him, he was attending a presentation by one of his former students, Elisabeth Soep; his pride in her accomplishments was so clear.

Dear Ellie and Family,

Dear Ellie and Family,

While words cannot heal your loss, they may help express the gratitude of generations of educators to Elliot for his profound inspiration, keen intellect, generous spirit and kind guidance. His thoughtfulness, dedication and insight positively influenced his many, many students and, in turn, their students. May you find some solace in knowing that his ideas and ideals, both his words and his actions, caused us to pause and ponder and eventually to create education that brings art to life. He will be greatly missed by the educational community.

Wishing you peace during this time of grief,

Sarada Diffenbaugh, PhD ’92

Founder, Mount Madonna School

I am an Art Teacher trained

I am an Art Teacher trained in the DBAE model and other Eastern teachings. Eisner has been my constant companion over my 40 years career as an Arts educator and artist. Currently, I am reading for a PhD in art teacher education and reflecting on the limited value society has placed on the Arts. Thank you Elliott Eisner for your wisdom and insightful ways that have shown me how to illuminate all that is powerful in Visual Arts. It is wonderful to know the ripple effect your teachings have had to the furthest corners of the earth. Rest in peace knowing you have touched so many lives and made a difference to this world.

We have lost a stalwart in

We have lost a stalwart in terms of an educational leader. I remember well reading the works of Elliot Eisner when working on my doctorate at Indiana University and for many years afterwards. He legacy will be forever.

I believe that Elliot Eisner

I believe that Elliot Eisner was a serious scholar deeply committed to the critical examnation of the arts in education, and to the crucial role of the arts in our culture and, by extension, in our schools. It is my hope that his influence on the curriculum and on the way it is taught will only grow.

Elliot Eisner leaves an

Elliot Eisner leaves an extraordinary legacy.

Through his writing, lecturing and teaching over 50 years or so, he has made an immeasurable contribution to our understanding of the intrinsic value of the arts in education. Successive generations of arts educators have been infected by Elliot’s intellectual curiosity about non-verbal ways of representing experience. Always he got straight to the heart of an issue; he never nibbled at the edges of an argument. His long-standing relationship with the Institute of Education, University of London will be fondly remembered by colleagues in the Department of Art and Design Education, who greatly valued his support.

I shall remember Elliot for his warm friendship, his generosity of spirit and his engaging company during many visits to London.

Roy Prentice, formerly Head of Art and Design Education, Institute of Education, University of London

Some months after I graduated

Some months after I graduated from the GSE and returned home, Elliot told me that he would be staying at Stanford Overseas in Stuttgart for some time in 1974. I came down from Mannheim U to see him, and we met with students to talk about academic life in Germany. I mentioned that Stuttgart is known to be the origin of the Waldorf school movement, which was founded Sept. 7, 1919 by Rudolf Steiner. Elliot was so excited that I arranged for him to visit with [Waldorf] students, teachers and administrators. I will never forget the spark in his eyes when we went to a class of nearly all ages performing music. The very young were hitting on the table while older ones played horns and violins.

Although my way into Industrial and Organizational Psychology somehow originated at Stanford, my admiration for an art educator like Elliot never vanished. We easily had much to talk about during my visit to Stanford some years ago.

Lutz F. Hornke, professor emeritus of industrial/organizational psychology, RWTH Aachen University, Germany

I am deeply saddened by the

I am deeply saddened by the loss of this inspired and gifted man. My work as a creative arts adviser in Sydney has been guided, inspired, disciplined and informed by his extensive work. His books, his papers and his wholistic person will never be forgotten. Elliot made all the connections through his deep understanding of the arts. Spirit, intellect, the aesthetic, culture, emotion and the brain were understood and became one through the artistic process. Thank you so much for touching my life and work. My prayers and thoughts to your family and colleagues.

I was a student of Elliot

I was a student of Elliot Eisner's in 1989-90 and was thrilled to have written a chapter in one of his books. I remember vividly that during one class he brought in a beautiful stainless steel bowl and just put it in the middle of the table and had us admire it as a work of art and design. I will never forget how inspired I was by his passion for simple beauty. He provided an anchor for my studies in the School of Education — there was plenty of intellect, but he was the artistic heart. Over 20 years later I am still in public education and try to bring to my own students and my own school that same passion for what cannot always be measured.

I met Prof. Eisner through

I met Prof. Eisner through Ellie; we attended ceramic classes together for many years and became good friends.

Prof. Eisner's writings and lectures inspire me. His vision educates us and redefines the mission of educators. His contribution to civility will be carried on by students of his students into the future of humanity.

Prof. Eisner was central in

Prof. Eisner was central in shaping my educational outlook in 1995 while working with him in my studies in the Stanford Teacher Education Program. I am deeply saddened to hear of his passing. As education takes a turn away for his ideals in many areas of the U.S., I find myself a similar lone wolf pushing for an expanded view of what comprises meaningful learning, to include dimensions beyond concrete knowledge and skill measurable by standardized tests, but to include elements of creativity, intuition, and cultivation of the heart. His work lives on in mine, and all the others he touched.

Dr. Eisner was my advisor for

Dr. Eisner was my advisor for my master's program in 1989. I took all of his classes and treasured his every word. He profoundly inspired me as a student and thinker. I'm saddened by his passing and so grateful for his life.

I have just now learned of

I have just now learned of Eliot's death from Bob Donmoyer and send my warm thoughts and condolesences to Ellie and the family. My husband Michael, treasured his friendship with Eliot from the days of his Standford sabbatical in 1977-78. We haven't been able to share many moments over the years since then, but the memories I have are of laughter over shared meals and real intellectual connection over long discussions. Getting to know Eliot was, for Michael, a wonderful part of that sabbatical year.

I can appreciate Elliot

I can appreciate Elliot Eisner's passion for the arts--now that I advise credential candidates and have had first hand experiences with the issues he championed. If we emphasized what makes education fun for students--the arts--I believe we would produce more successful students.

Elliot taught one of the first classes I took in the educational psychology program, and the class seemed like I was taking a foreign language at the time because I had been teaching in the health sciences. Reading his biography and reflecting on the public debates in education, I would love to relearn that foreign language he was teaching.

Dear Mrs. Eisner and Family,

Dear Mrs. Eisner and Family,

I am so sorry to hear about the passing of Professor Eisner. As you know, he was my advisor, and was the only one more passionate about life, learning, and humanity than I was at the time. For this, I will always be grateful! Professor Eisner possessed the incredible gift of being able to hone in on the crux of an issue, break it down, and build it right back up before your eyes in the blink of an eye. His bravery and boldness in pushing the establishment and all of us who looked up to him was extraordinary. And his refusal to let us forget about our ultimate responsibility: to create a more humane educational system was his glory.

We were privileged to sit

We were privileged to sit next to the Eisner’s at the San Francisco Symphony for several years

and witness Professor Eisner’s deep joy and involvement in the music. We will miss him. We

send Mrs. Eisner our warmest regards and sympathy.

very inspring

very inspring

My first graduate school

My first graduate school class was with Elliot--curriculum theory. He set the tone for the rest of my graduate studies at Stanford. He taught me much about how to imagine and re-imagine curriculum, how to appreciate connoisseurship, and how to think about concepts and new ideas in light of the old. I think what I appreciate most about having known Elliot, though, was his model of how to live a good life--intellectually, aesthetically, and in the company of others. I will carry Elliot with me in my thoughts always.

My deepest condolences to Ellie and your family.

To Dr. Elliot Eisner's family

To Dr. Elliot Eisner's family and the arts community: I am so very sorry for your (and our) loss! Dr. Eisner was a great man in the realm of arts education who contributed much to the field. His legacy will, no doubt, live on in the hearts of many arts educators, researchers, and scholars. May his memory be eternal.

It is nearly midnight in

It is nearly midnight in Houston and it is Elliot's birthday. I had meant to find Ellie all day, not knowing what to say or how. Everything about Elliot was, for me, large and wondrous. I miss him and cannot imagine my next visit to Stanford as not including a fine moment with my old, young friend. I understand my great good fortune for having known him.

I was fortunate to have the

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to have him as a faculty member and mentor my first year of graduate school. He helped me link my STEM interests to the world of art and to his approach to evaluation and research. My thoughts are with his family who were also very kind to me when I was a graduate student.

Indeed, I interacted with

Indeed, professor Eisner is missed. His ideas and his committed presence were inspiring. I interacted with professor Eisner after meeting with him during various Arts Advocacy forums and events. I often use his quotes, such as ”Curriculum is the mind-altering device”. In fact, I use it as the foundational principle for co-creating special authentic scaffolding for overcoming the lack of music literacy, in order to use music as the center of the healing modalities.

I admit having not just discussions, but fiery intellectual arguments with him, and it was fun, since he was a well-equipped conversationalist. It is sad that he did not see the implementation of his efforts to create the reform of the educational system, in order to balance emotional and intellectual development, and thus, to increase the value of the Arts and Music education. However, this strive has to be reinforced from all other parts of the society with the important re-evaluation of the emotional perception of the outer and inner reality, equally balanced with the intellectual perception.

The purposes of advocacy for universal access to the Arts and Music education and therapy for ALL is easier to grasp from the realm where the Arts and music have the effect of healing and urgency for transformation (in addition of the developmental capacities). In fact, the disrupted by trauma/stress balance of intellectual and emotional processing results into dysfunctional and paralyzed cognitive process, causing both temporary and localized blind spots of various nature, at times turning into the perpetual delusional mindset that reflects the wide shift of the pendulum from the balance into emotional detachment from the reality or into dominance of anxiety and hyper vigilance... And the balancing function of the sensory system through the Arts and Music practice is one of the most powerful manifestations of their transformative abilities that restore clarity, focus, polyphonic vision, symphonic prioritizing, creative production of solutions ”out of the box”, development of abstract cognition that affords the break through moral and ethical blind spots and arrival to the broader horizons from limited tunnel vision, among many other advanced functions otherwise unattainable or hard to reach.

This balanced approach to education has to be in place, in order to allow everyone the opportunity to align and to attune through human hearts with the primordial physical phenomenon of the Universal Field of Global Heats Coherence that links us all together, based on the same electromagnetic frequencies of the human hearts and of our mother planet. In this significant effort Arts and Music practices play the indispensable role of providing the conceptual metaphor-based language of THE EMBODIED EXPRESSION OF THE FELT SENSE for self-communication and self-awareness, critical for metacognitive perception and SELF-knowing of what is to be healed in the realm of the heart’s trauma, in order to eliminate its closure, the blocks to its function in the capacity of ”a portal” to partake from and to contribute to the nurturing Field of Oneness.

The current universal calamity of debilitation of the sensory system, based on the cumulative personal, societal and inherited unpacked emotional trauma, isn't recognized, and yet is the widespread epidemic that serves as the underlying root problem for most of other failures, dysfunctions , paralyzed solutions etc.

And finally, the very field of clinical psychology that is charged with the solutions in this domain of helping overcome various blind spots of imperfect human mind isn't capable to solve them with the current flawed approaches:

how can verbal-only modalities of clinical psychology be expected to solve the emotional issues of unpacked past trauma, if it is hard (if possible) to verbalize it adequately ?!

Thus, the role of Arts and Music education and therapy is most crucial in maintaining the sensory system to resume its lost functionality to inform our self-preservation instinct that had been failing among generations of out ancestors for centuries to protect our Human race from following the path away from evolution, but toward self-destruction and demise instead. That is why, the restorative process of sensory reactivation thorough the Arts and Music expression is a matter of sustainability for our Human race (not a luxury or an ”elective”, and especially not commercialized entertainment, as distorted through the current corporate misuse of these ancestral gifts of overcoming the blind spots of evolutionary young and still evolving human brain).

Manifestation of Professor Eisner’s ideas into reality would serve to finally honor his legacy of dedicated Arts advocacy. Perhaps, a dedicated fund with his name could help inspire the following of his footprints in ever challenging climate for Music and Arts during the time of increasing cataclysmic changes in our society that had become the reality, due to the absence of the attention to the humanities he had been so passionate about