Raise the status of schoolteachers, Stanford leaders say

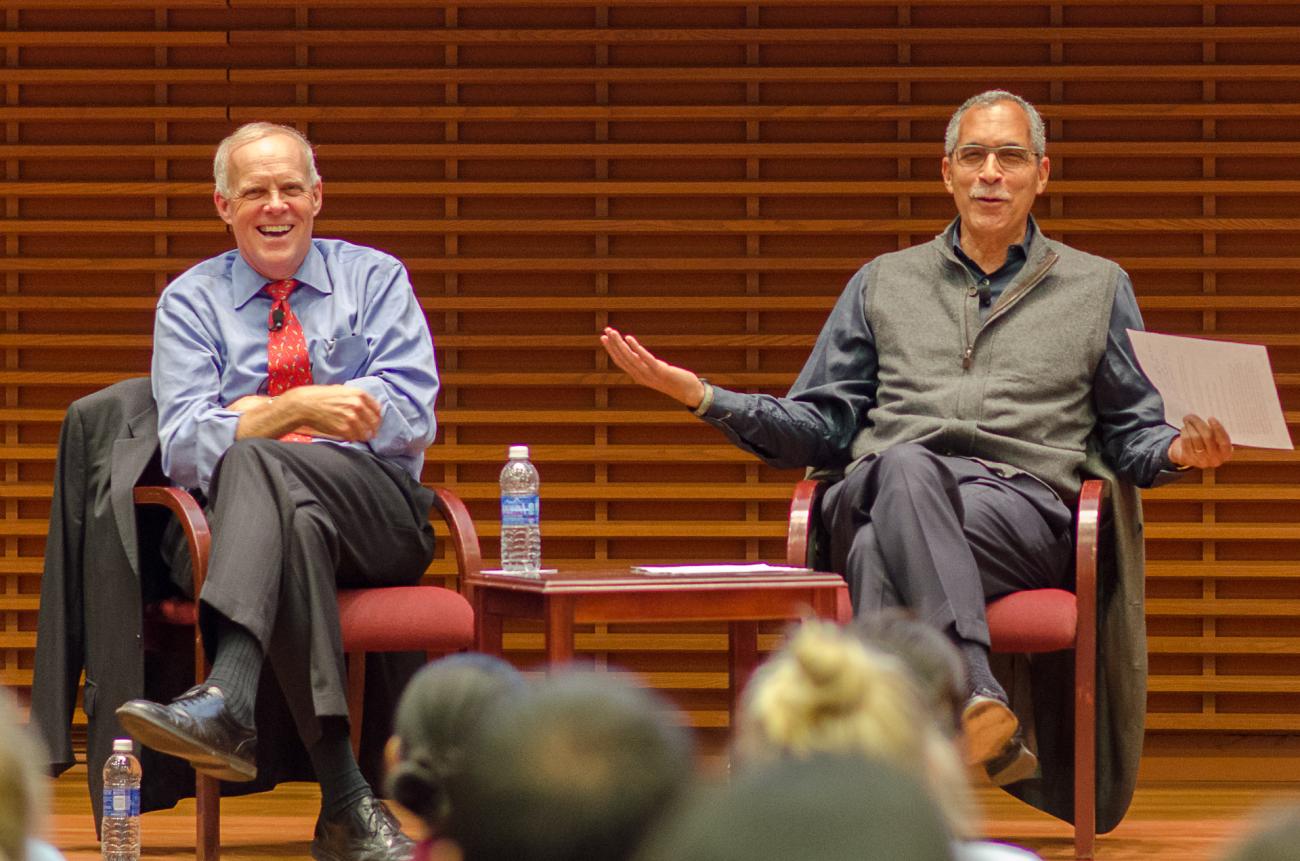

Society needs to place more value on teaching and schools need to help revamp the teaching career as part of an effort to attract the most talented students to the field, concluded a panel of experts, including Stanford President John Hennessy, during a discussion on jobs in education.

"I think we have to re-professionalize the teaching corps," Hennessy said. "We have to train great people. I think we, as a society, need to change as well. We have to put more value on it."

Hennessy joined Claude Steele, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE); Michael Kirst, president of the California State Board of Education and Stanford professor emeritus of business administration and of education; and Professor Rachel Lotan, director of the Stanford Teacher Education Program, for a discussion organized by the Stanford Pre-Education Society, or SPREES.

Julia Quintero, the founder and president of SPREES, a new club to encourage and support students interested in education, moderated the event, which included a roundtable discussion and questions from the audience.

"We understand that careers in education are often overlooked by students at elite institutions like Stanford," Quintero said. "We are here to change that. And the first step to change is sparking a conversation."

The panelists agreed that low pay and low prestige discourage many high-achieving students from going into careers in education, particularly teaching.

Other formidable obstacles include how poorly funded some schools are, Steele said, which leads to difficult teaching experiences.

"We talk about teachers as if they're supposed to be heroes, sacrifice themselves," he said. "I think as citizens we need to make [teaching] a much more attractive situation, a much more likely-to-succeed situation."

Raising standards for aspiring teachers, evaluating their performance on the job more effectively and paying them more would certainly help raise the status of teaching, the panelists said.

Teaching is complex, intellectual work, Lotan said, that "should be high status, should be paid well."

Having high-quality teachers, Lotan said, is part of creating a stronger workforce.

"Teaching is the profession that makes all professions possible," she said.

The key to having good teachers is having good preparation programs, she said. Aspiring teachers who attend highly competitive programs are better prepared and more satisfied with their careers.

Lotan noted, for example, that teachers from rigorous programs tend to stay in the profession longer, which ultimately is better for students. A recent study showed that after five years, when nationally only about 50 to 60 percent of teachers are still in their jobs, 75 percent of graduates from the Stanford Teacher Education Program are still teaching.

Lotan said teaching should be thought of as a political and moral act.

"When we decide why we teach, we are making a political decision," Lotan said. "We are expressing our vision and our goal for the future of society."

And the future of society depends on good teachers, Hennessy argued.

"If we really want to make sure the next generation has the kinds of opportunities that I think this country can offer, if the ladder that enables somebody to go from a very poor beginning in a family up to real achievement in the U.S. is going to be maintained, it's going to begin in K-12," he said. "We as a society owe all our young people a decent start at education."

Hennessy noted that many U.S. teachers come from the lower one-third of their college class compared to teachers in other countries, who come from the top third.

Getting more undergraduates from schools like Stanford into teaching could have a profound effect, particularly for lower-resourced schools that often can't attract the best trained teachers.

However, the panelists noted that teaching is only one of many possible careers in education for highly talented students.

Kirst listed dozens of companies, nonprofits, think tanks and other institutions where GSE graduates now work, including the Rand Corp., Mozilla Foundation, Apple Inc. and UNESCO. And he mentioned programs at the school that cater to students interested in careers in policy, technology and business.

"Education is a gigantic industry," Kirst said.

Steele also emphasized opportunities in research – both as a career choice but also to help boost the status of education professions. As in the case of medicine or law, education should be rooted in research, Steele said.

Research "can revolutionize the approach we take in schools," he said.

The GSE and the Education and Society Theme House at Stanford co-sponsored the panel.

Quintero said SPREES plans to hold more events throughout the year.

"My classmates so deeply admire you and respect you," she said while thanking the panelists for their participation in this debut event. "So to hear you encourage us to pursue careers in education is no small thing."