Stanford Principal Fellows program supports school leaders

Barnaby Payne stands outside Abraham Lincoln High School (Photo by Norbert von der Groeben)

Barnaby Payne stands outside Abraham Lincoln High School (Photo by Norbert von der Groeben)

What's striking about Barnaby Payne is he never seems to sit down.

At lunch, Payne, the principal of Abraham Lincoln High School in San Francisco, walks the neighborhood checking on his students as they fill up on nearby falafel, deli sandwiches and Taco Bell.

During breaks in class periods, he stands in hallways, greeting students with handshakes, high-fives and hugs. Meetings can occur under doorways, leaned against lockers, or traveling between school activities.

Even in his office, his feet don't get much rest. His computer is on a standing desk.

"You want a sense of what's happening in your building, with the students, staff and teachers," Payne says. "You can't get that sitting around."

Research shows a direct link between student success and school leadership. In fact, studies demonstrate that leadership is one of the most important influences on achievement — second only to teaching.

Yet little attention has been given to cultivating highly effective principals. Only in the past several years have scholars and policy makers focused on the practices of more successful principals, and districts focused on their support.

"The job can really beat you down," says Payne. "There are a lot of challenges in public education."

Payne, 44, has spent 18 years as an educator in San Francisco schools, not including attending them as a student. He was an eighth grade American history teacher for eight years before becoming an assistant principal — first at a middle school, then at Lincoln, where he moved up to the top job in August 2009.

Located less than two miles from the ocean, in San Francisco's Sunset neighborhood, Lincoln serves about 2,000 students in grades nine through 12. Sixty percent of students qualify for reduced or free lunches.

Payne said his ascension to principal was a natural progression. He was drawn to leadership roles, for one. And he felt a special connection and responsibility to the students and schools — as a San Francisco-native, parent and teacher. When the well-loved and highly respected principal before him at Lincoln retired — a person Payne considered a mentor — he decided to "throw my own hat into the ring."

About a year into his position, he was selected to participate in the Stanford Graduate School of Education’s Principal Fellows Program for early-career school leaders. As part of the program, he meets one weekday a month at the university with other principals in the San Francisco Bay area for a day of research presentations, discussion, problem-solving and, occasionally, a shoulder to lean on.

"As a principal, you can feel isolated, even if you have a supportive team at your school," Payne says. "The fellow meetings give you an opportunity to reflect, to recalibrate and to refocus. It creates a professional fraternity that is unique."

***

Started in 2008, the Stanford Principal Fellows Program focuses on building principals' capacity for skillful and strategic leadership and figuring out ways to increase success and equity at schools.

Each fellowship lasts three years, and a new cohort begins this fall. So far, about 70 principals have participated, including 14 from San Francisco, which cover almost every high school in the city. The program complements an extensive partnership between San Francisco Unified School District and the GSE that aims to integrate research, scholarship and professional development with daily practice in and long-term management of a major urban school district.

At the fellows’ meetings, principals dive into cases and research presentations with Stanford faculty and other experts, wrestling with the challenges of teaching English language learners, opening access to honors courses, ensuring discipline and safety, overcoming race and class barriers, strengthening teacher leadership, and assessing performance.

They've heard from Chip Heath, for example, and other professors of organizational behavior at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, on leading change in an organization. Larry Cuban, GSE professor emeritus, has discussed how to manage political demands with instructional and organizational leadership.

Principals also listened to Professor Geoffrey Cohen, of the GSE, on how stereotypes can threaten academic achievement, and Professor Carol Dweck, of psychology, on how student mindsets affect outcomes. Several GSE faculty also have explained ways to make teaching and assessments more equitable and powerful.

Stanford Drama and GSB Lecturer Dan Klein has taught improvisation, with a repertoire of behaviors that can increase organizational effectiveness. Principals have said work with the Stanford “d. school” has prompted more effective faculty meetings and planning.

"The program gives insanely busy principals some time, space and resources to strengthen their leadership insight and skills," says Gay Hoagland, GSE director of Leadership Programs and founder of the fellowship.

Schools today require principals who can skillfully manage both instruction and a very complex organization, in a context of rising demands, diminishing resources and often chaotic politics. Think of principals, Hoagland says, as the CEO, COO and CIO of their school.

The fellows program offers relevant knowledge and examples, including the invaluable expertise of the principals themselves. They teach each other, sharing and analyzing their own successes and failures. They also seek, from the program, the entrepreneurial tilt of Silicon Valley, and a focus on equity practices that gives them more courage to take risks.

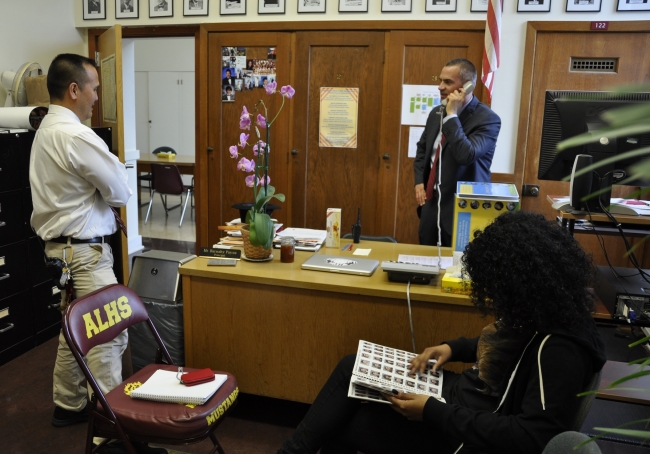

Barnaby Payne (center) works in his office at Abraham Lincoln High School (Photo by Brooke Donald)

Barnaby Payne (center) works in his office at Abraham Lincoln High School (Photo by Brooke Donald)

Payne's voice bellows down the main hallway of Lincoln as he warns students to get to class. "Just go," he says, finger pointing. "Go. Be marked present. Learn."

There are no bells to signal tardiness. Payne has worked in schools with bells and without and says he continued a 'no-bell' experience at Lincoln because he believes it's important that the students learn responsibility without that trigger.

"There are no bells in life, or in college," Payne says. "They know where they're supposed to be. I want them to know we expect them to figure it out."

Creating a climate hospitable to learning is one of the "best practices" of highly effective principals, and is discussed during fellow meetings. Shaping a vision of academic success, improving instruction, using data for school improvement and strengthening leadership in others are also hallmarks of a good principal.

"It's an old school way to think about principals as the people sitting in an office waiting for badly behaved students to be sent to them," Payne says. "Yes, discipline is still an issue but it's certainly not the dominating thing I think about."

What has been on the top of Payne's agenda is figuring out ways to not only get his student population to graduate but to also be ready for college.

According to recent data, only about 38 percent of California's high school graduates are eligible for the state's public universities.

"We're working hard on figuring out how to push every child toward excellence," Payne says. "We need to make sure our curriculum and class offerings can get them there and we need to make sure our teachers are supported in carrying out that curriculum."

Gay Hoagland, left, director of the Stanford Principal Fellow Program, speaks with a fellow during a session on the Stanford campus (Photo by Terrance Turner)

Gay Hoagland, left, director of the Stanford Principal Fellow Program, speaks with a fellow during a session on the Stanford campus (Photo by Terrance Turner)

Each fellowship class has no more than about 24 principals. Payne's group extended its three-year commitment to four years, eager to carry on their learning. Besides the monthly meetings, each class also attends a summer retreat.

The small cohort size and three-year format allow the principals to gain solid trust, challenge each other, steal successful examples and freely exchange ideas. And it’s a particular boost for principals from the same district, such as SFUSD, who can share ideas about district-wide policies.

"This is not just a workshop," says Ericka Lovrin, principal at George Washington High School, also in San Francisco. "You're thinking about systemic change. It's keeping creative juices flowing."

Principals can point to changes in practice based on what they learned during program meetings, reporting, for example, that their planning is more strategic; leadership teams take stronger action; hundreds of underserved students are now succeeding in honors courses; teachers are leading classroom change.

Materials and research findings from program sessions are often passed to other administrators, extending the fellowship's reach deeper into a district.

Though it is hard to tease out impact on students from the many complicated factors in play, Hoagland says research documents that student achievement in the fellows’ schools has improved faster than the state trend.

For his part, Payne says he adjusted the way students prepare for tests after a discussion during a fellows meeting about so-called stereotype threat. He says he worried that the way his school separated students in order to give them extra help may, in fact, have set those students up to do poorly.

"All I needed was to be reminded of this phenomenon — have a chance to think about its implications," Payne says. "Once I was given that time, we realized there were simple changes that we could make that could have big impact."

Fellow Kevin Kerr, principal at San Francisco’s Balboa High School, says the monthly meetings allowed reflection with people who were experiencing similar problems and challenges, and got "you moving in the right direction."

The Principal Fellows Program also gives Stanford faculty an opportunity to hear from school leaders and to serve practitioners with their latest theories and research.

"It goes directly to a mission of the GSE to provide the research knowledge and evidence critical to improving schools," Hoagland says.

Barnaby Payne works at his desk at Abraham Lincoln High School (Photo by Norbert von der Groeben)

Barnaby Payne works at his desk at Abraham Lincoln High School (Photo by Norbert von der Groeben)

Payne's day can end as late as 9:30 p.m. if there are parent, teacher or district meetings, school performances or sports games or other projects. He and his wife, an educator at San Francisco's June Jordan High School, split duties taking care of their two young daughters.

Payne, who earned the rank of Eagle Scout when he was 16, says it is easy to feel like you're drowning. "You have to learn to breathe underwater. You have to somehow grow gills," he says, only half-joking.

The fellows program has helped him take necessary pauses for air.

He's learned to manage time for both the scheduled and the unannounced visitors. And he more easily sees the bigger picture, despite often needing to handle apparent minutiae.

On a recent day, he talks with the dean of students about a computer system affecting truancy letters sent to parents; hears student complaints over grading on a test; records a video to Pharrell's "Happy" for an upcoming assembly; and discusses curriculum for students with autism with a district representative.

"We really want to be on the cutting edge of what we can do for these students," he says.

In the hallway, as he takes a moment to greet students, one gives him a small cake —a thank you from the student's mother for the work he's doing. Another, carrying a cafeteria tray of food, asks Payne for a fork — which he gets from his office.

"When it comes to the kids," Payne says. "No request is too small."

For more information on the Principal Fellows Program, click here: http://principalfellows.stanford.edu/