Two families in the same region yet a world apart on reading

Houses in the Gicumbi district, where Jolly and Flora live. (Photo by Elliott Friedlander)

Houses in the Gicumbi district, where Jolly and Flora live. (Photo by Elliott Friedlander)

Flora is 9-years-old; Jolly a year younger. Flora, who lives on a steep hillside, mostly spends her time out of school doing chores: cooking, fetching water, gathering firewood. There is no time to play. No time, or materials, to read at home.

Jolly lives at the center of the village, not too far from Flora but not as isolated. Her father is a local teacher. Her mother dropped out of school after fourth grade but is active in the community. She has few chores. It's not uncommon for her to play cards or sing and dance with her six siblings. Reading is encouraged. Writing is practiced.

Flora and Jolly (names changed) are the subjects of a detailed ethnography conducted by Stanford researchers as part of a study into the culture of literacy in rural Rwanda and methods to boost children's reading skills.

Back to: "Reading in Rwanda: Researchers map the state of literacy in rural Africa"

The girls were chosen at random from 467 homes surveyed for the larger research project. The girls were observed for one week by Michael Tusiime, of the University of Rwanda, in collaboration with the Stanford team of Elliott Friedlander, Saima Malik and Professor Claude Goldenberg.

Friedlander says the families revealed very different perspectives on the role of literacy in the lives of Rwandan children.

“One family deemphasizes reading and writing as, essentially, a luxury to be confined largely to school. This is likely closer to the norm in rural Rwanda," Friedlander said. "The other family, Jolly's, was much more the anomaly. They see literacy as the necessity of a better life and infuse reading, writing and math wherever possible at home.”

The first observation the team noted was in the dearth of literate materials in Flora’s home, where the entirety of available printed material consists of a small bible, a one-page prayer, two cards posted on the wall and one notebook Flora used only during school days. Tusiime witnessed no reading or writing whatsoever in Flora’s home over the course of the week long observation.

Meanwhile at Jolly’s house, there was a stack of books, pens and pencils. The books included teacher’s guides and photocopies of children’s books written in Kinyarwanda, the local language. Letters, words and numbers, scribbled in chalk in a child’s hand, were visible on a wall and a window shutter outside her house.

“My children have never seen me read because we have nothing to read in this house,” Flora’s father said, as documented in the ethnography report. “I’d rather spend the little money I earn to secure their physical needs than buy them newspapers to read.”

Friedlander says it's essential that a family environment supports literacy in order for the child to become literate. "These include the physical spaces where the kids live as much it does the attitudes and practices around reading and writing,” he said.

Higher aspirations

While her mother was being interviewed, Jolly removed a book and pen from the researcher's bag and wrote some sentences. (Photo cropped to protect student's identity.)

While her mother was being interviewed, Jolly removed a book and pen from the researcher's bag and wrote some sentences. (Photo cropped to protect student's identity.)

Common to subsistence farming, Flora’s day was filled with chores. She had to fetch water as many as four times a day—a 45-minute walk down the mountain and longer still coming back uphill carrying heavy buckets. If not fetching water, she might be found feeding cows, collecting firewood, cooking or caring for her younger siblings—anything but reading and writing.

“We only do homework when we are at school, or we do it with other children on our way from school,” Flora said.

Flora also was instructed to leave the room when Tusiime spoke with Flora's father, as her father felt that was not appropriate for children to speak with adults. Such limits likely affect Flora's vocabulary and language growth, Friedlander said.

Down in the village, on the other hand, Jolly’s father, the teacher, brings chalk home from school and creates space for his children to practice writing. Jolly did homework with her siblings. When they played games, Jolly’s elder sister wrote the names of the players and their points on a small piece of paper. Jolly counted score.

Jolly, also, is encouraged to speak with her mother.

“There was a low level of support for reading at Flora’s house, and a high level for Jolly,” Friedlander said. “Jolly also had greater literacy skills, more confidence in her reading abilities and, perhaps as a consequence, higher aspirations for her future.”

For girls, in particular, the challenges are compounded. Marriage, not school, is emphasized. Yet in Jolly's house, Jolly's mother was the most passionate of all about her children’s education.

“In this family, we do not tolerate any child who does not show effort in reading or in education in general,” said Jolly’s mother. “I strongly believe my children can also have a better life when they complete their education, and that starts by reading.”

In Jolly's house, time is specifically set aside to do homework. Chores could even be skipped to read.

But Flora's father didn't feel like he had that option. He spoke of wanting to education his children but needing their help around the farm far more. He and his wife viewed education and reading as useful, but beyond the family’s financial means in the long term.

Some of the villagers Tusiime spoke with see education as “an investment that gives no returns” unless completed at the highest levels, Friedlander said. This, in turn, reinforces a culture of low expectations and limited aspirations. Flora’s mother spoke of children stopping their education at primary school.

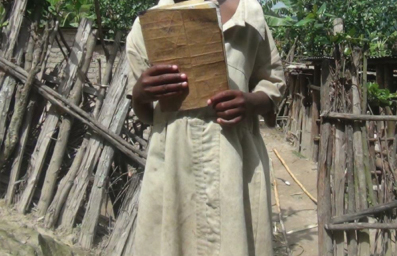

Flora holds the only book she could find in her home. She uses the same book for Kinyarwanda, Maths and English. (Photo cropped to protect student's identity)

Flora holds the only book she could find in her home. She uses the same book for Kinyarwanda, Maths and English. (Photo cropped to protect student's identity)

“Would you continue investing your resources in projects where you don’t foresee profit?” she asked.

In contrast, Jolly’s family prizes literacy and academic achievement and provides the resources necessary to learn, whatever the cost. Both parents in her home can read and she has older siblings in school, so role models abound for Jolly and the family goes out of its way to provide basic reading materials.

Friedlander emphasized that, as with Flora’s family, the problem is not a community-wide disdain for education or the educated.

“These parents know that education matters, but many lack the basic understanding that they should read to and talk to their children—things you and I take for granted,” Friedlander said. “If we can shift the culture, even a little bit, small things can add up to a big change.”

Back to: "Reading in Rwanda: Researchers map the state of literacy in rural Africa"