New report shows historic gains in pandemic recovery for many U.S. school districts

A new report by researchers at Stanford and Harvard shows that U.S. students achieved historic gains in math and reading during the 2022-23 school year, the first full year of recovery from the pandemic.

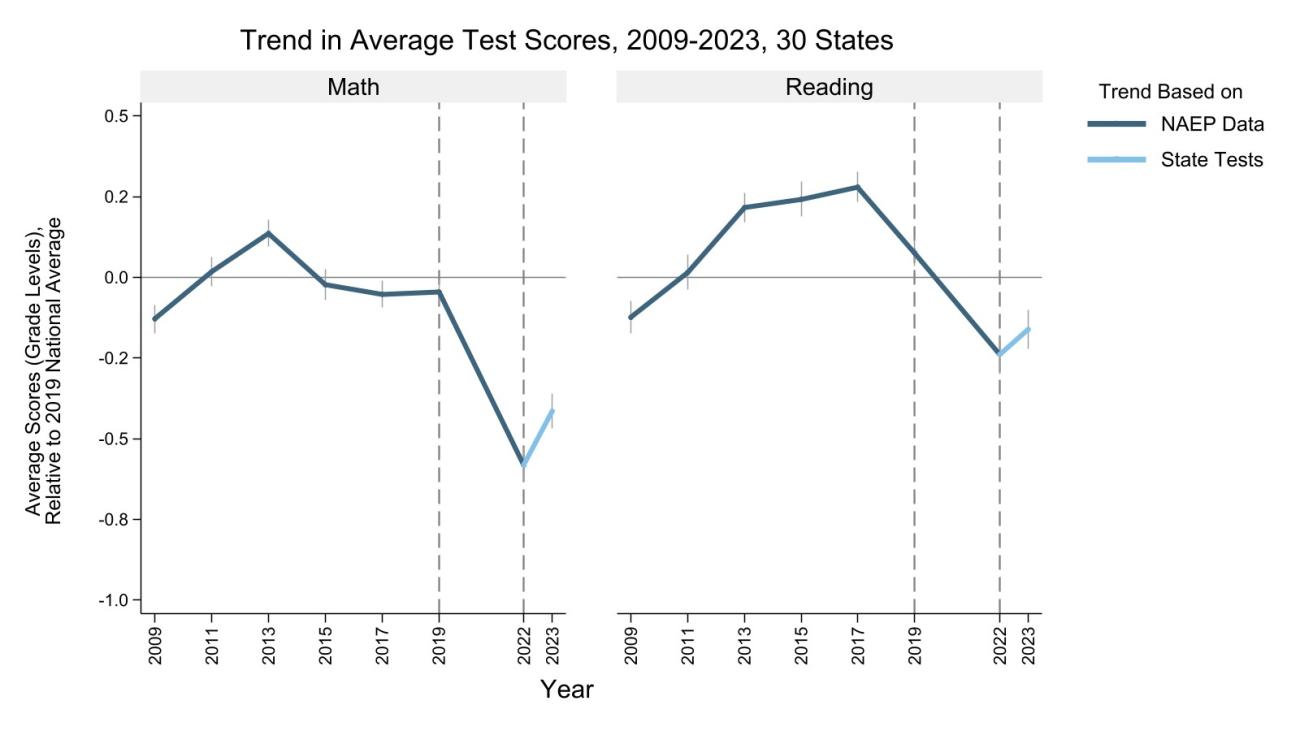

The report, which measures the pace of academic recovery during the 2022-23 school year for school districts in 30 states, finds that students recovered about one-third of the original loss in math and one-quarter of the loss in reading. These gains significantly exceed what students would be expected to learn in a typical year, based on past trends.

Students in one state, Alabama, returned to pre-pandemic achievement levels in math, while students in three states reached 2019 levels in reading. But students in a majority of the states in the study remain more than a third of a grade level behind pre-pandemic levels in math, and students in almost half of the states are that far behind in reading.

“Students overall haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels of achievement,” said study co-author Sean Reardon, the Professor of Poverty and Inequality in Education and faculty director of the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University. “But clear progress is being made.”

The new data also reveal that achievement gaps between high- and low-poverty districts have widened since 2019, the result of larger initial losses in poor districts and the slower recovery of poor students within the average district.

The report was published Jan. 31 as part of the Education Recovery Scorecard, a collaboration between researchers at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) and the Center for Education Policy and Research (CEPR) at Harvard.

The researchers followed up on findings they released last year showing that, between spring 2019 and spring 2022, the average student in grades 3 through 8 had lost the equivalent of half a grade level in math achievement and a third of a grade level in reading.

“We should thank teachers and principals and superintendents for what they’ve done for American schoolchildren in the last year. Their efforts have led to strikingly large improvements in children’s learning,” said Reardon. “But we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the recovery has been uneven, and we have a long way to go.”

Measuring losses and progress

The report draws from the Stanford Education Data Archive (SEDA), a comprehensive national database run by the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University that includes reading and math test scores from every public school in the United States. The database, first made available online in 2016, has been used by researchers and policymakers to study patterns and trends in educational opportunity across the country and by race, gender, and socioeconomic conditions.

For this analysis, the researchers used standardized test results from roughly 8,000 school districts in 30 states. The remaining 20 states were not included either because they changed their state assessments since 2022 or because they did not provide sufficiently detailed data on their websites.

To measure the original losses from the pandemic, the researchers compared test scores from spring 2019 and spring 2022. To measure the recovery, they compared scores from spring 2022 and spring 2023. Across all 30 states in the study, students recovered about 30 percent of the original loss in math and 25 percent of the loss in reading.

While students in Alabama returned to pre-pandemic levels in math by spring 2023, students in 17 states remained more than a third of a grade level behind their 2019 achievement levels. Students in Illinois, Louisiana, and Mississippi returned to 2019 levels of achievement in reading, but students in 14 states remained more than a third of a grade level behind.

During the 2022-23 school year, students recovered on average about one-third of the pandemic loss in math and one-quarter of the loss in reading. The gains are significantly more than students would be expected to learn in a typical year, based on past trends from the National Assessment of Educational Progress. (Chart courtesy of the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University)

An uneven recovery

The report illustrates disparities in the impact of both the pandemic and the recovery. Achievement gaps between high- and low-poverty districts widened during the pandemic, with students in high-poverty districts losing the most ground.

The researchers found that the recovery so far has done little to close these gaps. “In many states, the recovery is being led by wealthier districts, which lost the least during the pandemic,” said Reardon, who is also a faculty affiliate of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning and a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. “Students in poor districts are, on average, well behind where they were in 2019.”

States in which achievement gaps have widened the most are Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Michigan, according to the report.

Congress provided a total of $190 billion in federal aid to K-12 schools during the pandemic, with most of it targeted at high-poverty districts. The funding program is set to expire in September 2024, and according to the U.S. Department of Education, roughly a third of the funds remained unspent as of fall 2023.

The report recommends ways for state and local agencies to allocate the remaining funds, including expanding summer learning opportunities this year and contracting for tutoring and after-school programs.

“Despite strong gains last year, most school districts are not on track to complete the recovery this spring,” said Thomas Kane, faculty director of the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University and a co-author of the report. “District leaders should use these data to check their progress and rethink how they spend the remaining federal relief dollars.”

Additional collaborators on this project include Erin Fahle, Sadie Richardson, Julia Paris, Demetra Kalogrides, Jie Min, and Jiyeon Shim (Educational Opportunity Project); Daniel Dewey, Victoria Carbonari, and Dean Kaplan (Center for Education Policy Research); and Douglas Staiger (Dartmouth College). The research was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Citadel founder and CEO Ken Griffin and Griffin Catalyst, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Faculty mentioned in this article: sean reardon