What do teens care about? Stanford education researchers uncover top concerns in letters to presidential candidates

In the months leading up to the U.S. presidential election in 2016, thousands of teenagers around the country wrote letters to the candidates about the issues that mattered most to them, posting their letters onto a public website. Too young to vote, these middle- and high-school students crafted passionate arguments about everything from homelessness and immigration to abortion and climate change.

For a team of researchers at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), the collection of more than 11,000 letters had the makings of a hefty data set—one that offered a window into what young people care about and how those issues vary by school demographics.

Dozens of the topics kids chose to write about were significantly linked to socioeconomic factors, the researchers found in a new study published in the American Educational Research Journal.

Immigration, police and race were among those more likely to be addressed in letters from schools serving predominantly lower-income students and students of color. Guns, school costs and gender issues were more likely at schools serving more affluent and white students.

What’s more, a close look at letters from schools in five states showed marked differences in the way students argued their case, suggesting that teachers’ instruction plays an important role in what counts as evidence.

“We wanted to shed some light on kids’ concerns, especially underserved students across the country, and see how they varied,” said Amber Maria Levinson, PhD ’14, a research associate at Stanford GSE with the Technology for Equity in Learning Opportunities (TELOS) Initiative and one of the study’s authors. “We saw a lot of commonalities but also some interesting differences.”

Antero Garcia, an assistant professor at Stanford GSE, led a team of researchers analyzing more than 11,000 student letters written to the presidential candidates before the 2016 election. (Photo: Jim Gensheimer)

A classroom project

The research study emerged from a nationwide classroom initiative called Letters to the Next President, which was first launched during the 2008 presidential campaign by the National Writing Project (NWP), an educational nonprofit.

A 2016 reboot, Letters to the Next President 2.0, drew more than 11,000 letters by teenagers from 321 schools in 47 states. With their teachers’ approval, the students posted their letters on a website hosted by the NWP and KQED, a San Francisco Bay Area PBS affiliate.

Levinson—whose work focuses on the use of media and technology to support learning, especially among underserved youth—has discussed potential research collaborations with KQED over the years. When KQED research manager Denise Sauerteig proposed using the letters for a study, Levinson was intrigued.

“KQED had created this great website that lets you peruse and search the letters, but it doesn’t give you an overview of what the data says, what the letters say, how they fall out across different demographics and different states,” she said. “It’s a terrific resource, and we wanted to take it further.”

As they took a closer look at the archive, the Stanford researchers realized they had their work cut out for them.

“When the kids post their letter online, they tag it to show what category it goes into,” said Antero Garcia, an assistant professor of education at Stanford GSE and lead author of the study. “But it’s an open field—the kids can write any tag they want.” A student who writes a letter about preventing cruelty to animals, for instance, could tag it animal rights, animal abuse, animal testing or something else. “One might just say animals. Or animal lives matter. Or there could be a typo, so it says aminals.”

The research team had the unenviable task of sorting through the thousands of letters and streamlining the categories, then grouping the letters appropriately. Next, they gathered statistical data for the schools and communities where the student letter-writers lived.

“We don’t know any data about the individual students, like race or ethnicity or gender, but we know the school site where every letter was written,” Garcia said. “From there we could look at national data to figure out socioeconomic status and some electoral information, including whether the precinct went for Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump in 2016.”

Linking topics to school demographics

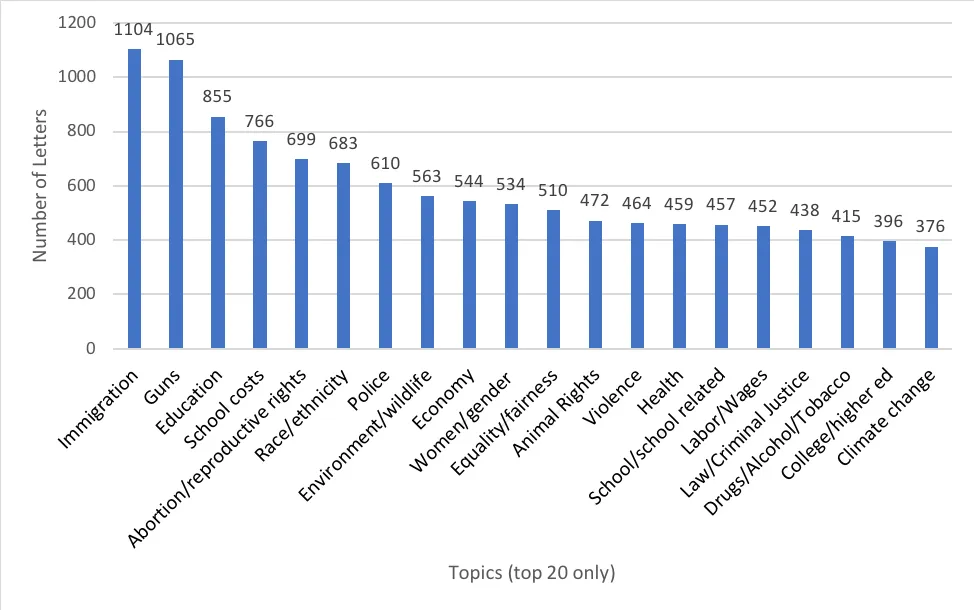

There was no single topic that overshadowed all others, the researchers found, though some were more prevalent that others.

Immigration was high on the list: Nearly 10 percent of students tagged their letter with a term in this category (including border patrol, deportation, and others). Gun violence was another leading topic.

“And this was before the Parkland shooting, when you would imagine that high school students began to get very involved in this issue,” said Levinson. “But in 2016, it was already one of the top concerns.”

The researchers identified a number of connections between letter topics and school demographics. First, the topics of immigration, race, discrimination, police and violence were prevalent among letter writers overall but significantly more likely to be written about in letters from schools that serve a majority of both students of color and lower-income students (where more than half receive free or reduced-cost lunch).

The cost of college was also a prevalent issue in the letters overall, but kids from more affluent schools serving predominantly white students were more likely to write about it, the researchers found.

“We can’t really say why that’s the case, but one of our theories is that those students are being positioned more strongly to attend college, so it’s more at the forefront of their minds,” said Levinson. “It’s possible that students from schools serving predominantly lower-income students or students of color have other issues that are more at the forefront of their minds—it’s not that they’re not worried about college costs or not thinking about going to college, but maybe they’re more worried about other issues that are prevalent in their communities.”

Letters categorized under guns (including those tagged gun control and second amendment) and women’s/gender issues (including feminism and gender wage gap) were also more prevalent among more affluent schools with majority white students.

Researchers grouped more than 11,000 student letters into 69 categories.

Other analyses of the letters are currently in the works: Levinson and Garcia are doing an in-depth study of the subset of letters focused on immigration, while GSE doctoral students Emma Carene Gargroetzi (who also coauthored the AERJ paper) and Lynne Zummo are analyzing those addressing climate change.

How students made their case

Beyond looking at patterns among topics and school demographics, the researchers also closely analyzed letters from schools in five swing states—Ohio, Nevada, Michigan, North Carolina and Florida—to study how the students constructed their argument.

“We looked at the kinds of evidence these students used,” said Levinson. “Did they cite sources, or did they state something as fact without citing it? Did they use personal experiences or data? Did they appeal to the readers’ emotions, did they make an ethical appeal, or did they make a logical appeal?”

Among the letters from the five schools they examined (all socioeconomically diverse and serving high percentages of students of color), the most common form of argumentation was an appeal to logic. Nearly two-thirds of the letters appealed to ethics, referencing moral standards or what is “right.” Only a quarter of letters made appeals to empathy, asking the reader how they would feel in another’s shoes. (A majority used more than one form of argumentation.) Most letters included some form of evidence such as personal experience, citations or unsourced data.

The form of argumentation and type of evidence used varied significantly across the five schools, suggesting that teachers play a central role in students’ understanding of what makes a convincing argument and what counts as evidence, the researchers said.

The letter-writing project offered a valuable way for young people—who aren’t able to vote—to make their concerns and opinions known, Levinson said. She hopes the project will inspire educators to think about new ways to approach civics in the classroom.

“We’re seeing so many powerful civics movements, with young people coming out and speaking strongly on issues they care about,” she said. “But these movements aren’t coming from schools. If we can make a stronger connection between the topics that kids are passionate about outside of school and what they’re doing in school, that only stands to make learning more meaningful.”

This study was funded by the Spencer Foundation. Caitlin Martin, MA '99, and GSE doctoral students Shadab Hussain and AJ Alvero provided additional research assistance.

Faculty mentioned in this article: Antero Garcia