Disrupting the college experience: Q&A with Stanford professors Mitchell Stevens and Michael Kirst

In "Remaking College: The Changing Ecology of Higher Education," co-editors Mitchell Stevens, associate professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education, and Michael Kirst, Stanford professor emeritus, argue that Americans need to rethink their understanding of learning after high school. The dream of the four-year residential campus is not a realizable one for many, they say, and "it may not even be a good idea."

The book challenges policymakers and others to consider a different model for higher education. Maybe college isn't a four- to six-year endeavor to be done in your early 20s; perhaps it's something you move in and out of your whole life. Maybe it doesn't even take place on a campus but through a series of online courses. And maybe you don't always get a degree but a certificate, proving excellence in a particular craft.

Scholars from a range of disciplines contributed the essays that examine the history, economics, philosophy and politics surrounding higher education. The book trains particular focus on broad-access institutions - community colleges, for-profit colleges and comprehensive public universities. The editors point out that these schools educate the most people and have the biggest challenges yet have been relatively neglected by scholars and the general media.

"But they're also some of the most innovative places," Stevens says, making them the perfect sites for rethinking what college should be.

Below are excerpts from an interview with Kirst and Stevens about the book, published by Stanford University Press. The project was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Why does college need reimagining?

Mitchell Stevens talks about remaking college. (Video by Marc Franklin)Stevens: A golden era of higher education is over. That's the period from the mid-1940s to about 1990, in which there was massive government investment in colleges coupled with almost complete institutional autonomy. That's no longer the case. Since 1990 we’ve experienced overall decline in government subsidy and higher costs, yet a growing demand for a college education. Inherited models aren't sustainable as they are, so it's necessary to come up with a new ways of providing, measuring and experiencing higher education.

Kirst: Just look at the funding. In California, for example, we give community colleges less per pupil than we do to high schools. And we have the least funding and resources at the institutions with the most needy students. We've stressed the four-year residential model and underinvested in community colleges, which are doing the lion's share of the work.

But the ideal "college experience" is the four-year model, correct?

Stevens: No. First, there's the exorbitant cost of residential delivery. There are also tepid learning gains by any direct measure. For some young people, four-year campuses can be dangerous in terms of substance abuse, depression and feelings of alienation. Also, some teenagers just aren't ready or able to commit to that because of money or family obligations. So the notion that the four-year residential model is the best way, the default way to experience college, is a problem. It's important that Americans embrace a much wider diversity of college forms.

Kirst: There is a problem - both in policy and in people's minds - with how college has been framed in the national conversation. We talk about needing to prepare everyone for college, but “college” currently is a loaded word that comes with implicit timelines and delivery expectations. What we want is a conversation about making quality higher education available in a wide variety of formats over the course of entire lives.

You say there is very little research on higher education outside of the four-year model. Explain.

Stevens: The majority of social science research of the last 50 years was built around an implicit expectation that it’s best to go to college right after high school, enroll full time unencumbered by paid work, and complete a bachelor’s diploma promptly. If that didn’t happen the analyst presumed some sort of failure—either of the student or the system. What we're suggesting is that that is a profoundly limited way of thinking about how people best move through the time and space of school.

As scholars, we've often held community colleges to standards of four-year completion and judged them on that basis, but community colleges are not designed like four-year institutions and are not built to serve the same kinds of needs. So why do we measure them by the same yardstick? The research agenda needs to change.

Part of the ambition of this project is to put more of the research capacity available at schools like Stanford in the service of improving community colleges and other broad-access schools.

Michael Kirst talks about remaking college. (Video by Marc Franklin)Policymakers, too, you argue, aren't looking at colleges in a comprehensive way.

Kirst: That's the point of Chapter 8 - why has so much attention and heavy-handed reform been aimed at K-12 while higher education has received such a lighter touch? The answer is that higher education enjoys much stronger public trust. The average citizen thinks K-12 schools are really in trouble. There's not a public sense that the problems of colleges are as deep as the book points out they are. And relatively few policymakers have even attended a community college or know one of them well, so those institutions are often invisible to influential decision makers.

How are broad-access institutions already being innovative and remaking higher education?

Stevens: They're much savvier with technology, for one. They embraced the web as a legitimate vehicle for instructional delivery years before the elite research universities did. The for-profit sector, especially, was way ahead in this regard. They match the rhythm of adult lives. They have lots of evening course times. They offer easy parking. Those little things matter a lot to people with jobs and children and hectic schedules.

Kirst: They recognize, too, that increasingly employers aren't just looking for degrees, they're looking for what people can demonstrably do. These schools offer multiple forms of credentialing. And many people who go to community colleges or for-profit schools aren't actually going for the degree. They may already have one. They're going for additional skills. In the book we're really making a plea for more public attention to these schools and recognition of the wide range of learning that can happen in them.

___

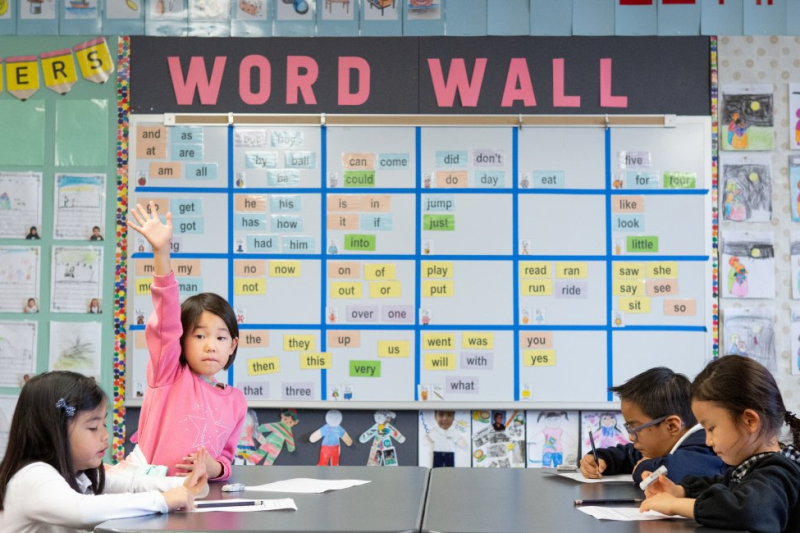

Photo: Hartnell College in Salinas, Calif. (John Phelan/Wikimedia Commons)