Stanford’s California World Language Project supports intensive summer program for middle schoolers

At first, the classroom seems no different. On an early morning in Sunnyvale, Calif., the teachers have gone over the agenda and instructions for the day, and soon pairs of middle-school pupils lean over iPads as they work on slides for final project.

Teachers check-in on students from time to time, facilitating learning and providing support when needed. Once the students have completed slides, they then digitally record their narration of the story.

While these types of instructional activities are the norm for a classroom abuzz with learning, what distinguishes this experience for students is that all the instruction and learning is done exclusively in Mandarin -- as part of an intensive summer language program sponsored by the California World Languages Project (CWLP) at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE).

Stanford Professor Amado Padilla is the principal investigator of the program, which gets federal funding from STARTALK, an initiative aimed at developing student interest in learning critical need foreign languages.

The Stanford/CWLP program is four weeks long and designed for non-speakers of Mandarin from diverse backgrounds, especially Latino, Padilla said. This year, it took place at Columbia Middle School in Sunnyvale.

The program is among several initiatives that GSE faculty worked on this summer to support learning and teaching. The Center to Support Excellence in Teaching (CSET) also conducted professional development with the Hollyhock Fellowship and the Summer Teaching Festival, for example, and Professor Deborah Stipek, who heads the Development and Research in Early Math Education (DREME) initiative, conducted a daylong workshop on effective leadership and instruction for Chinese preschool directors.

Many of these programs feature a blend of collaboration that supports learning and teaching on all ends of the process.

Duarte Silva, executive director of CWLP, said STARTALK provided two teacher candidates from the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP) with an opportunity to observe instructional strategies of veteran teachers while also supporting student learning.

“The STARTALK instructional team includes a powerhouse of teachers. One also is a STEP graduate herself and all of the teachers are graduates of the California World Language Project’s professional learning programs,” Silva said.

Culture and language

For first-time students like Joey, the first couple of days of the Mandarin immersion experience was overwhelming. However, she came to appreciate that she could “learn more this way.”

The teachers center the learning activities around a Silk Road Ambassadors themed curriculum. The lessons and instructional activities engage students as they journey the Silk Road and acquire the language and cultural practices that they have learned about or created during the course of the program.

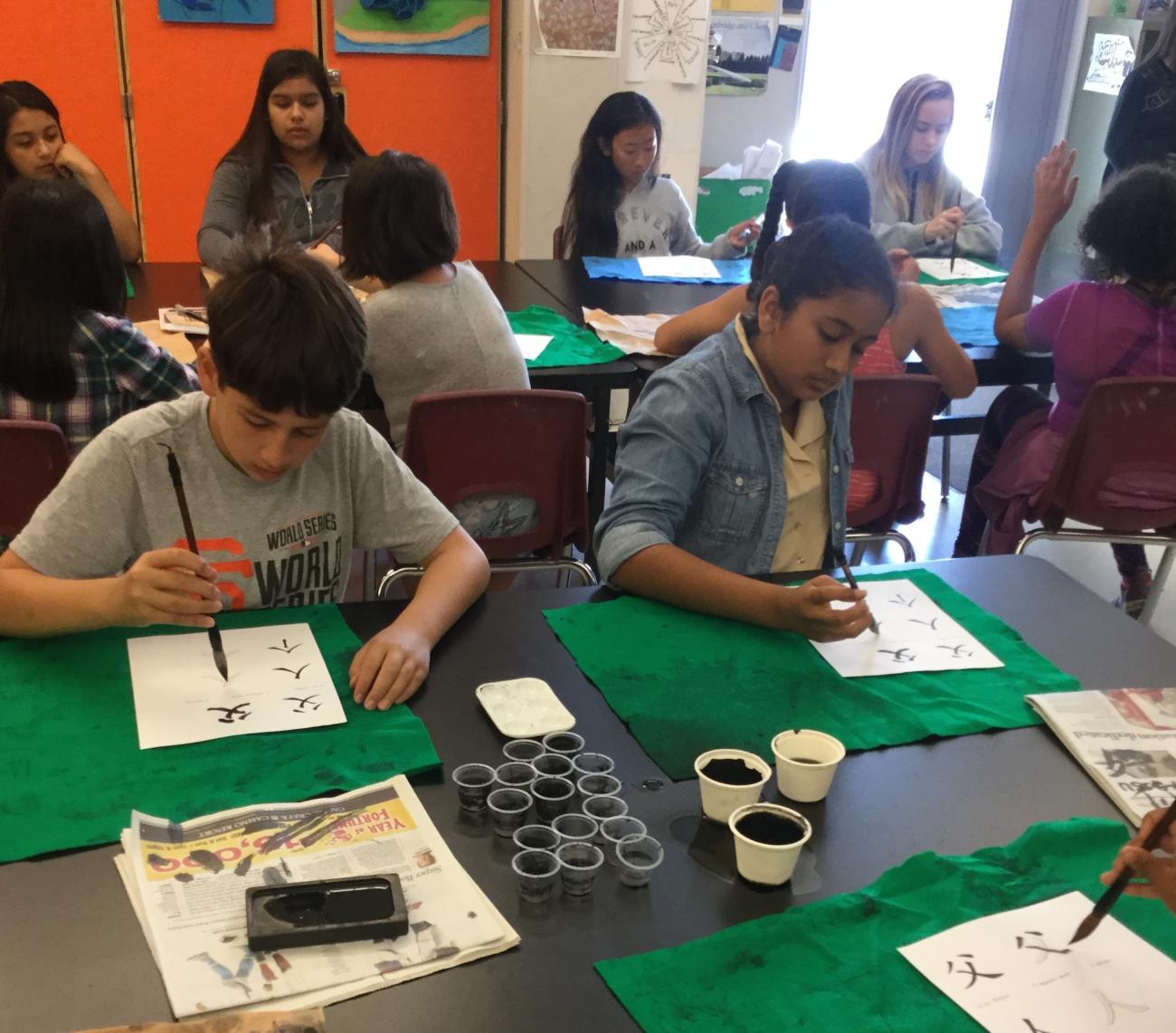

Without hesitation, the students most commonly report that the cultural activities are the highlight of the program. As part of a series of “cultural labs,” students are given exposure to different aspects of Chinese culture through lessons on areas such as paper-making (one of China’s inventions), calligraphy and Tai Chi, a form of Chinese martial arts.

The students also had opportunities to experience Chinese culture outside the classroom as well—and put their language skills to the test. During the third week of class, all 32 students traveled to San Francisco’s Chinatown for a field trip including a tour of Chinatown's landmarks and a history lesson on how the Chinese helped to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake.

Afterward, students ate lunch at a Chinese restaurant where they further applied the language skills they had acquired as students. The field trip ended with a chance for students to visit a variety of Chinese shops, which featured items such as jade, fans, coins and other items that the students had learned about in the program.

Padilla said STARTALK not only gives students an opportunity to learn Mandarin, but the program also opens students' eyes to what is possible in terms of language learning and culture.

“Due to the diversity of the participants, the program prompts students to reflect on their own individual cultural backgrounds as they learn about different Chinese cultural perspectives, practices and products and identify similarities and differences from their own,” said Padilla.

A few of the students have even returned for a second year, like Gavin. For Gavin, who is half-Chinese, the summer program has given him an opportunity to learn more about his heritage and that of his grandparents.

For Danielle, the STARTALK program has spurred her interest in languages, and she “hopes to learn more languages and become a translator.”

For many students who participate, the exposure to the language and culture motivates them to continue their Mandarin language learning through high school. Four high school STARTALK teacher assistants are even returning alumni of the program, and they said that they like that they can “help the next generation of students learn Chinese language and culture.”