Teaching ethnic studies: Four takeaways from Stanford education conference

Starting next academic year, high schools across the state of California must offer ethnic studies courses, and they will be a graduation requirement starting with the class of 2030. In a large and diverse state with nearly 2 million secondary students, districts are working on – and sometimes struggling with – how to effectively bring the coursework into their schools and create meaningful and high quality lessons that enrich and benefit students.

The 2024 annual conference of the Race, Inequality, and Language in Education (RILE) program at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) addressed this issue through a multi-day convening, “Exploring Ethnic Studies: A Collaboration Research & Training Event for Everyone.” The conference aimed to support California educators, administrators, and districts to implement the ethnic studies mandate, and featured two days of virtual panels with researchers and practitioners, followed by two days of in-person teacher professional development workshops with the Khepera Curriculum Group.

For the first time, the Stanford Accelerator for Learning was a collaborator on the event, having initiated a seed grant exploring new approaches to ethnic studies earlier this year as part of its Equity in Learning initiative. Ethnic studies is an interdisciplinary approach to learning about the histories, experiences, and cultures of marginalized groups that emerged from student activism in the 1960s. Research by Tom Dee, a professor at the GSE, has shown both short and long-term academic benefits of an ethnic studies program in San Francisco, leading to adoption of an ethnic studies mandate in the state.

While ethnic studies is a contentious topic in education, the conference sparked honest discourse between researchers, curriculum developers, classroom teachers, and teacher educators and raised key questions to consider as the subject is implemented in schools statewide.

Some insights from the conversations:

1. Ethnic studies can be transformative for students and society.

Eujin Park, an assistant professor at the GSE and faculty affiliate of the Accelerator, took her first ethnic studies course as an undergraduate. “It was revelatory and transformative, and gave me a new language and a new framework to understand my own experience and that of others,” she said. “It shaped the rest of my four years in college and the trajectory of my career and research.”

As a high school teacher for more than a decade in San Jose and East Palo Alto, where her students are largely Latino, Irene Castillon, MA '10, witnesses the benefit to her students of learning Mexican-American history. “I see engagement and love for learning, and there is a lot of question-asking,” she said of her students, crediting the connection of the course to student identities. She noted that students in these courses brought in stories of their lives and their families, and went above and beyond because they wanted to, not just for the sake of a grade.

“One of the most powerful impacts of ethnic studies is that it can create humanizing spaces in classrooms and in our society,” she said, and shared that several of her former students have now become ethnic studies teachers themselves, pointing to the multigenerational impact of the approach.

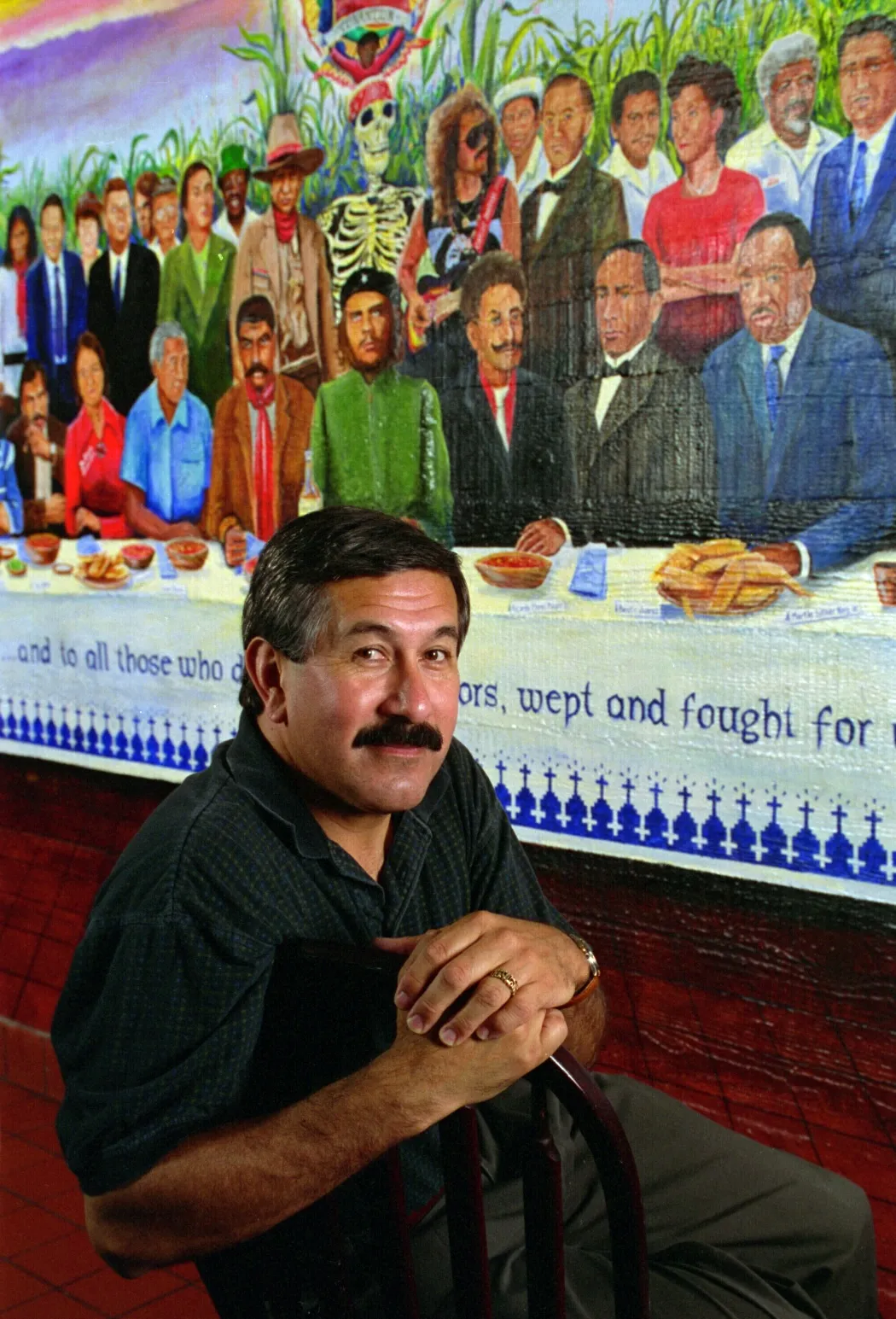

Albert Camarillo, a professor emeritus of history at Stanford, is widely regarded as one of the founding scholars of the field of Mexican-American and Chicano Studies. He reflected on his decades of experience teaching ethnic studies at the college level to students who rarely had access to these types of courses in high school.

“When you provide this information to students who are open-minded and thirsting for this knowledge, they are listening intently,” he said. “We can see today how race is still such a dividing idea used to drive fear and anxiety in the hearts of a lot of Americans. Don’t we as educators have a fundamental commitment to provide a basis for our students to be able to understand each other?”

Albert Camarillo, a professor emeritus of history at Stanford. (Photo: Linda A. Cicero / Stanford News Service)

2. Ethnic studies cannot be taught in a silo; it must draw upon students’ realities.

Several panelists expressed concern about the challenge of implementing ethnic studies successfully across the diversity of school settings in California, and highlighted the importance of ethnic studies courses that reflect students’ lived experiences, family backgrounds, and communities.

Tony Green, a 30-year veteran social studies teacher at Bishop O’Dowd High School in Oakland, has developed and taught Black Studies courses for years, drawing upon local history and community.

“In the East Bay, there is a rich legacy of Black community and I try to bring in elders as the foundation of the class,” he said. “They are a primary source to tie into African American history. Allowing community involvement builds on the richness of the content.”

Green has taken his students to see Bobby McFerrin as part of a lesson on the oral tradition of West Africa, leads an annual field trip to Marcus Books, the oldest Black-owned bookstore in the United States, and invites his students’ families to class to share their stories. “The more I bring in the community, the more the content and pedagogy changes,” he said.

Park sees potential for ethnic studies to make schooling more responsive to marginalized students and communities. “What happens when their knowledge and experiences become centered the way that ethnic studies demands that we do? What would it look like to seriously engage the funds of knowledge that communities hold? How can that transform California’s K-12 schooling?” she asked.

3. Teacher preparation and self-reflection are crucial in the implementation of ethnic studies.

Rita Kohli, an associate professor at the University of California, Riverside (UCR), coordinates the ethnic studies pathway of the university’s teacher education program. Her work has focused on building and strengthening the racial literacies of teachers, especially teachers of color. Kohli noted that between 85-90% of teacher preparation faculty are white, and traditionally, teacher certification programs talk little about race. However, this fall, every incoming teacher candidate at UCR will take the ethnic studies pathway course.

“Teacher education programs need to grow and be responsive – the ethnic studies pathway is a possibility for this to happen,” said Kohli. “But it will take the willingness of teacher prep program leaders, districts, and schools to grow in their understanding of ethnic studies.”

She also noted the danger of ethnic studies teachers, particularly teachers of color, being held responsible for all social justice and diversity work in their schools, which she has seen become stressful and draining for teachers she’s worked with. “What are the things we can do to invest in everyone’s racial literacy?” she posed to the group.

Castillon shared what it’s taken for her to become a successful teacher of ethnic studies. “Ethnic studies is the merging of the hearts and minds, and I think about ethnic studies as ‘a work of heart,’” she said. “Teaching is sometimes go-go-go. But it’s important to have pause moments to include families and the community to do this work.”

She cited self-reflection and consideration of identity and positionality as key. “Before teaching ethnic studies, teachers need to consider, ‘Who am I? What is my story? What do I need to learn and unlearn?’”

4. Researchers are key collaborators in developing ethnic studies programming.

Antero Garcia, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty affiliate of the Accelerator, is coordinating the Accelerator’s seed grant that funds new research on how to teach ethnic studies across school contexts. He described some of the in-progress research projects and reflected on the role of universities in supporting the implementation of California’s ethnic studies mandate.

“When it comes to setting our research agendas in academia, we need to consider: who does our work reach? How does it improve teacher practice? Who does this work benefit?” he said. Garcia urged researchers to consider both their research methods and dissemination to be most useful in classrooms. “If ethnic studies is about uplifting these communities we have worked with for years, do the ways we communicate that work fulfill that promise?” he asked.

Camarillo echoed that higher education needs to support ethnic studies implementation in high school, saying, “Ethnic studies is already being offered and is successful at universities in a lot of places, and collaborations between districts and universities are being established across the state.” He called upon both high school teachers and researchers to seek out and invest in these collaborations. “It’s a larger educational movement.”

Faculty mentioned in this article: Antero Garcia , Eujin Park