Dyslexic children show differences in brain reading region

We see not just with our eyes, but with our brains. A mosaic of specialized areas in a brain region known as the visual cortex interprets different sights, helping us identify everything from solid objects to the faces of our loved ones.

And, as we learn to read, our brains develop a region that specializes in recognizing the written word – it’s known as the visual word form area.

“We know this region exists only in the literate brain, but no one has determined how it emerges as children learn to read,” said Stanford University reading expert Jason Yeatman, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics, of education, and of psychology.

Prior research found low activity in the reading-specific brain region in people with dyslexia, but those studies mainly captured only single snapshots in time and left open many questions about how dyslexia plays out in the brain.

Yeatman’s team recently conducted brain scans in kids with dyslexia, both before and up to a year after an intervention to improve their reading skills. Yeatman was the senior author of the study, which appeared in Nature Communications in December. The study’s lead author is Jamie Mitchell, a graduate student in education.

Specialized gray matter

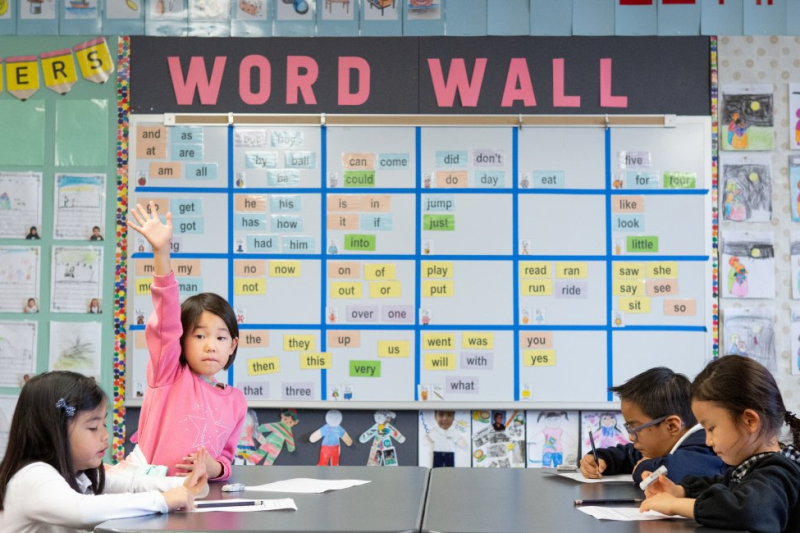

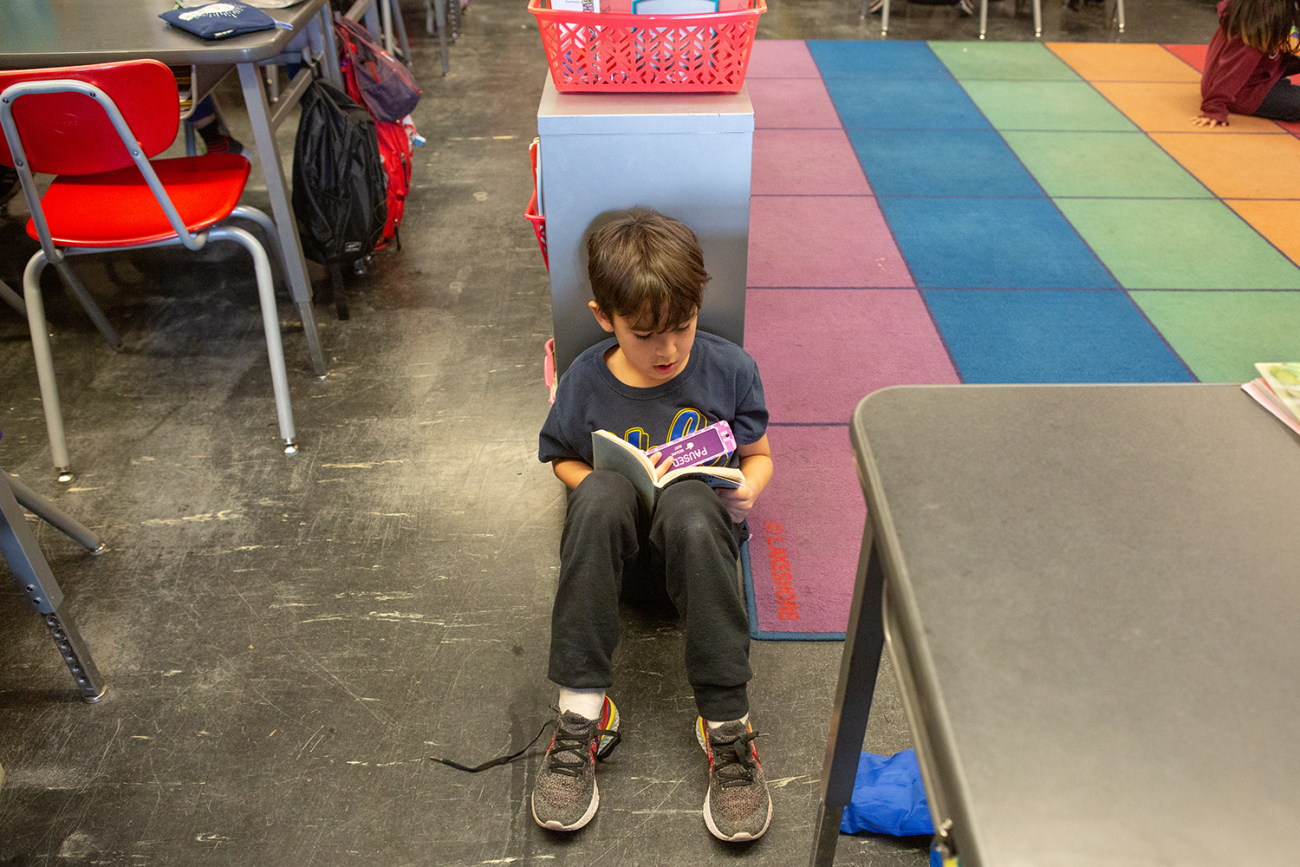

Dyslexia is a common learning disability – affecting 5% to 10% of the population – that makes reading challenging. People with dyslexia struggle to learn the letters of the alphabet and their associated sounds, to “sound out” words, to spell, and to recognize rhyming words, for example. (Many people with dyslexia remain undiagnosed, Yeatman said. He leads another Stanford University project to increase the proportion of kids who receive a timely diagnosis.)

Dyslexia can affect individuals with all levels of intelligence. It won’t resolve on its own; kids need instruction tailored to the condition.

Fortunately, education experts have developed effective, research-backed tutoring programs that help children with dyslexia become fluent readers. However, the interplay between brain development and learning remains largely unknown.

Normally, as kids learn to read, the visual word form area develops within the visual cortex, a large region of the brain’s “gray matter” located at the back of the head. The VWFA is a small part of the left side of the brain – ranging from pea-sized to about the size of a dime – that lights up on functional magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brain while people are reading. It has two subregions, one that responds to the shapes of words and another that also responds to their meanings.

In the Stanford University-led experiment, the researchers assessed brain activity in kids via functional MRI, performed up to five times over a year. Of the study participants, 44 were kids aged 7 to 13 with dyslexia who went through an intensive reading intervention. The control group included 43 children in the same age group who did not receive the reading intervention, of whom 19 had dyslexia, and 24 had normal reading abilities.

Smaller ‘reading area’ equals weaker reading

On brain scans conducted at the beginning of the study, the researchers found the VWFA in nearly all typical readers but detected it in fewer than two-thirds of the kids with dyslexia.

“One of our key questions was ‘Is the VWFA different in those with dyslexia?’” Yeatman said. “On that question, we have a very clear and resounding ‘Yes.’ In kids with persistent reading struggles, we see that this key part of the brain involved in rapid word recognition is either missing or much smaller.”

Among kids who had a detectable VWFA, the region was smaller on average in children with dyslexia than in typical readers. The size of each child’s VWFA was linked to his or her reading ability: Kids with a smaller VWFA had weaker reading skills. The neural response to seeing words – how strongly the region “lit up” during reading – was also weaker in kids with dyslexia than in typical readers.

After the initial brain scans, some children with dyslexia received the reading intervention, an intensive program that enabled them to improve their reading levels by about one grade level over eight weeks. This group’s reading scores improved significantly, while over the same period, kids with and without dyslexia who did not receive tutoring showed no change in reading ability.

After the reading intervention, the researchers could detect the VWFA in more children with dyslexia, while the chance of detecting this area in kids who had dyslexia but had not gone through the reading program was unchanged. “It’s as if evidence-based intervention builds this region in the dyslexic brain,” Yeatman said. The VWFA also grew larger in children who had completed the reading intervention; it did not grow larger in the control group.

However, at the end of the study, kids with dyslexia still had, on average, smaller VWFAs than typical readers, and the relationship between reading ability and the area’s size persisted. The neural response in the VWFA also remained weaker in children with dyslexia.

In short, even once the children with dyslexia received enough tutoring to close the gap in their reading scores, their brains still had subtle differences from those of typical readers.

“We see that the visual word form area is plastic; it is malleable to experience,” Yeatman said. “When struggling readers spend eight weeks receiving an intensive, evidence-based reading intervention, on average, their VWFA grows larger. So, the intervention is not only improving their reading, it’s also building the brain circuit. That’s very cool.”

The findings open new questions about how best to help children with dyslexia, such as whether more tutoring would eliminate the differences seen in the brains of these kids, he said.

“Many kids with dyslexia, even as their reading improves, have persistent struggles,” Yeatman said. “This brain difference may be at the root of those continued challenges.”

Researchers from the University of California at Santa Barbara, Vanderbilt University, and UC Irvine contributed to the study.

The research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers also received a donation of time and resources from the Lindamood-Bell Learning Center to provide the reading intervention for study participants.

This story was originally published by Stanford Medicine.

Faculty mentioned in this article: Jason Yeatman