An excerpt from Myra Strober's new memoir, "Sharing the Work"

Myra Strober, a Stanford labor economist who studied gender issues, childcare and feminist economics, led a trailblazing career that required a balancing of her maternal duties with her academic ones. She was a rising scholar during the 1960s and 1970s, breaking down workplace and societal barriers while also raising a family. Below, Strober shares lessons learned in an excerpt from her recent memoir, Sharing the Work:

My secret path to motherhood

Myra Strober

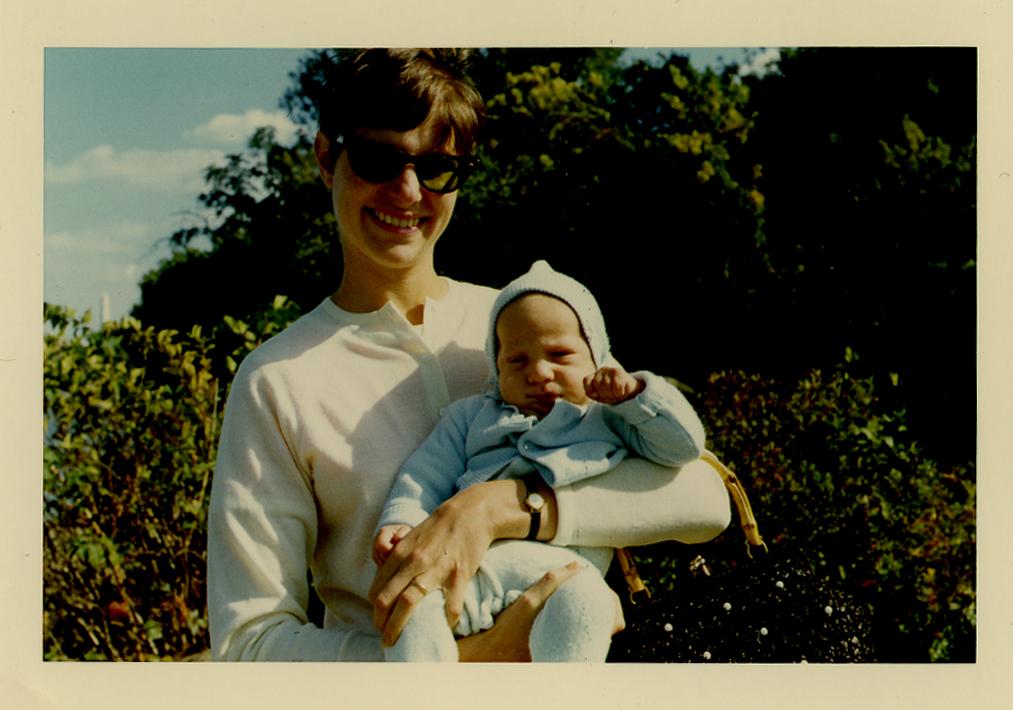

Just a few weeks after I pass my general exams in economics, I realize that I very much want to have a child. I finally feel relaxed after months of tension, and it’s as though a big blanket has suddenly dropped from heaven and wrapped my entire being in longing for motherhood. I feel an almost physical ache, and my arms suddenly yearn to hold a baby.

Fortunately, my husband Sam also wants a child (he’s been ready for some time now), and we begin talking seriously about timing. We want to wait to have a baby until after he’s finished his medical internship and I’ve finished my doctoral thesis. By then we expect to be living in a slightly larger place than our tiny Boston apartment.

In a few months, I become pregnant. My due date is July 15, 1969, just two weeks after we’re slated to move to Bethesda, Maryland. I’m thrilled, but when we call my mother-in-law, she’s beyond thrilled. She’s ecstatic.

The pregnancy is not easy. I’ve heard of morning sickness, but my nausea seems to last until after dinner instead of ending at lunchtime. Fortunately, I’ve finished taking classes, and am just working on my thesis because I need to make several trips a day to the MIT restroom. I’m also exhausted, sleeping nine and ten hours a night and taking frequent naps in the library. Nothing seems to help—not Saltines (they leave a salty taste in my mouth and a lot of crumbs), not the anti-nausea medicine (it gives me a headache), and not plain hot water sipped slowly (yuck). But many things make it worse, including climbing the four flights of stairs to our walk-up apartment. I just endure it, reminding myself that it’s finite and a small price to pay for this incredible life inside me.

After about three months, the nausea diminishes and I decide that I’ll announce my pregnancy at school. Each morning, as I drive from Boston to Cambridge, I tell myself that this will be the day. I picture exactly where I’ll be and exactly whom I’ll tell. But I’m never able to picture positive reactions, so when I get to my designated time and place, I remain fearfully silent. MIT is so male, and being pregnant is so quintessentially not male. Of its more than six thousand students, only four hundred, or a little under 7 percent, are women: about two hundred undergraduates and two hundred graduate students. In my PhD economics cohort of about thirty students, there are only two women, and I’m the only one who’s married. A few of the men are married, but most are single and a year or two younger than I. I’m starved for female companionship. The secretaries and women administrators see me as odd, and while they greet me politely, they rarely engage me in their conversations.

Some 15 years after my MIT experience, Rosabeth Moss Kanter will coin the term tokenism for the strangeness I feel. But I have no term for it except the one I coin for myself—honorary man.

I’m afraid that if I tell my professors about my pregnancy, they’ll take away my honorary male status—withdraw their support for my job search or refuse to serve on my thesis committee. Whatever they might do, none of it seems good.

There’s no one I can talk to about this. I have no friends in this situation, and I don’t know any older women who have preceded me. I think about talking to Mom but reject that idea pretty quickly. She would be far too anxious. When I ask Sam, he says he doesn’t really know what I should do. Finally, I rationalize my silence, deciding that it’s probably best to go on the job market without publicizing my pregnancy. As a woman, I’m an unusual candidate to begin with. A pregnant woman might be too much for a prospective employer.

I arrange to go to D.C. and give job talks at three universities on three successive days. I’m five months pregnant, and I buy a loose but stylish suit for the interviews. I ask the saleswoman if she can tell I’m pregnant. She says she can’t. Sam says he can’t either. I feel like some kind of espionage agent with my little secret, but I’m really not showing at all. I’m also not at all nauseated anymore. I’m still more tired than usual, but I sleep well in the D.C. hotel and am full of energy every morning when the job talks and interviews take place.

Although I’ve made only slow progress on my thesis because of my nausea, I still have enough material to present preliminary results. Faculty and students are clearly interested in my work, and nobody seems to have difficulty with my being a woman. A month or so after my interview at the University of Maryland, the school makes me an offer, and I accept enthusiastically.

Finally, I begin to show. At first I just loosen up the waistband on my skirts, but after a while I need to buy maternity tops. None of my fellow students seem to notice, although I wonder if they think I’m just getting fat and are too polite to say so. As for the faculty, I think the idea that one of their students might be pregnant is so foreign that they can’t see my pregnancy, even when it’s right in front of their eyes. Or maybe they can, but, like me, can’t bring themselves to talk about it.

However, one day when I stand up in front of the labor seminar to give a talk on my thesis, the secret is out. When I’m finished, Professor Abraham Siegel comes up to me.

“I see you’re pregnant. Congratulations,” he says, in a most straightforward way.

I sigh with relief, smile, and thank him. But I don’t fully appreciate his attitude until years later, when I see women colleagues and graduate students in male-dominated fields berated by male colleagues and thesis advisors for becoming pregnant: “You could have been a star, and now look what you’ve gone and done.” MIT may have had few women, but the faculty in economics supported me all the way.

Once Professor Siegel opens the pregnancy conversation, that seems to make it safe for the other faculty and students to chime in, and everyone who says something is congratulatory and supportive. Soon even the women secretaries begin to talk to me. I can hear them thinking: well, she’s a woman, after all.

Myra Strober is the founder of what is now Stanford’s Clayman Institute for Gender Research and one of the first women on the faculty of Stanford's Graduate School of Business. At the Graduate School of Education, she also researched gender issues in the labor force. The subtitle of her new book is, What My Family and Career Taught Me about Breaking Through (and Holding the Door Open for Others). During her career, she was committed to studying and thwarting sexism, in the workplace, in academia, and at home.