Higher education is in a "period of great experimentation" in the field of online learning, Stanford President John Hennessy told an audience in Berkeley last week, adding that he is confident its successes and failures will lead to new approaches to teaching that will benefit students.

"We're going to invent the future," Hennessy said, speaking during the opening Q&A of an online summit held March 7-8 at the University of California, Berkeley, "How Technology Impacts the Pedagogy and Economics of Residential Higher Education."

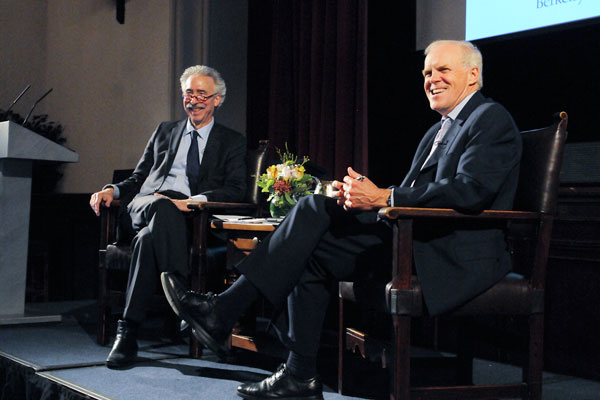

Speaking during a "fireside chat" with UC Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas B. Dirks, Hennessy said that colleges and universities will be taking a more scientific approach to online learning than in the past, relying on their schools of education to measure student learning and to provide feedback.

"I'm actually pretty confident that we're going to come out with pedagogical approaches that are truly a step forward in terms of helping our students be better learners – and that will really be refreshing," Hennessy said.

The invitation-only summit, which attracted more than 150 people, was sponsored by UC Berkeley, Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford.

The event featured panels of online-learning leaders from across the country, including senior administration officials, and professors of education, human computer interaction, cognitive studies and sociology.

Candace Thille, an assistant education professor and senior research fellow in the Office of the Vice Provost for Online Learning at Stanford, organized a panel on learning analytics that featured faculty from Columbia University and Carnegie Mellon University.

The conference opened with Chancellor Dirks and President Hennessy sharing the stage in Chevron Auditorium in the International House, a program center and campus residence at UC Berkeley.

Dirks, an internationally renowned historian and anthropologist who became UC Berkeley's 10th chancellor last year, said the two universities had dramatically shaped the energy, innovation, prosperity and cultural life of northern California.

"To be working together now in thinking through some of the issues that are part of our virtual future – a virtual future that will continue to be based and predicated on the actual, physical, materialized campuses that we work in and benefit from – is a great opportunity for all of us today," Dirks said.

Noting that Hennessy was a computer scientist – among many other accomplishments in the field of technology – Dirks said he would use their meeting to pitch him a series of questions from a humanist perspective.

Dirks noted that technology makes it possible to expose students to a wide variety of learning opportunities.

"What one can see potentially happen is that online technology will further enhance what we can do on our campuses," Dirks said. "We can flip classrooms, because we can also then have those follow-up seminars. We can give that 'high touch' in person, as well as true customized forms of technological supplementation."

Hennessy agreed.

In response to questions from Dirks, Hennessy said massive open online courses (MOOCs) – as well as video conferencing – present a great opportunity to provide something of real value in professional education and to generate enough income to cover their costs.

Within the general public, he said, "communities of learners" could form around MOOCS.

"Imagine that 'Book of the Month Club' becomes 'Course of the Month Club'," Hennessy said. "With a little bit of technology, a community of learners self-assembles around a course and forms a group. They do peer grading. They interchange. They exchange conversations and they learn the material together. I think we'll see this happening. It would be a wonderful thing and great for the world."

Hennessy also discussed the challenges faced by instructors whose MOOCs attract students with a dynamic range of abilities – some without the background necessary to succeed, some who would like to move more quickly through the material and others who need to move more slowly. Sometimes instructors don't know there's a problem until exam time.

At UC Berkeley and Stanford, he said, faculty members design exams to challenge students.

"Now, take that exam to a school where perhaps the students are not quite as capable and give them that exam and you're going to crush them," he said.

"So we've got to figure out how to tailor and customize these courses much more appropriately for the level of the student, the rate at which the material is going to go, the rate at which the students are going to move. Over time, this will happen. We've just got to continue to push it there, and make the adaptation to individual ability and to the classroom setting in that particular institution."

Hennessy said one thing that MOOCs do very well is "educate the educators" in other parts of the world, allowing them to use the material to prepare courses for their students.

In response to a question from the audience, Hennessy said some faculty have reported that more students are attending classes when they have "flipped" the classroom – delivering lectures online and meeting in the classroom for one-on-one interaction and hands-on projects. While those early indicators are positive, he said, controlled experiments would be the key to understanding how well students are mastering the material in those settings.

At Stanford, the Office of the Vice Provost for Online Learning advances faculty-driven online learning initiatives and research, providing exceptional educational opportunities to Stanford students by transforming the way learning is organized in its classrooms and far beyond them.

Stanford fosters collaboration with other universities by sharing course material, data-driven research and source code for enhancements to its open-source platform Stanford OpenEdX. It also makes courses available to lifelong learners everywhere through Stanford Online and continually experiments to improve what it does through creative use of technology, sharing its findings with the rest of the world.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.